The Banishment of Untermeyer

In February 1950, CBS launched What’s My Line?— a quiz show that would become one of TV’s first big hits. Produced by Mark Goodson and Bill Todman, the program had initially been conceived under the working title Occupation Unknown, highlighting its core premise: a celebrity panel had to guess the occupations (the “line” of work) of ordinary contestants through a series of yes-or-no questions. Most guests were everyday people with unusual jobs, but each episode also featured a “mystery guest” (a famous figure whom the blindfolded panel had to identify). The appeal lay not only in the game itself but in the witty banter exchanged between the panelists and the moderator, John Charles Daly, a respected network newsman with a suave demeanor.

What’s My Line? episodes were preserved through kinescoping— the process of filming a TV monitor during a live broadcast.

In its early days, What’s My Line? experimented with scheduling, airing live in various time slots before settling into a Sunday 10:30 p.m. rhythm in October 1950, where it remained for the rest of its seventeen-year run. It soon drew an estimated 14 million weekly viewers and would go on to win multiple Emmy awards for “Best Quiz or Audience Participation Show.” This success reflected the broader “dawn of the age of television,” as mid-century audiences were eager to experience new forms of entertainment.

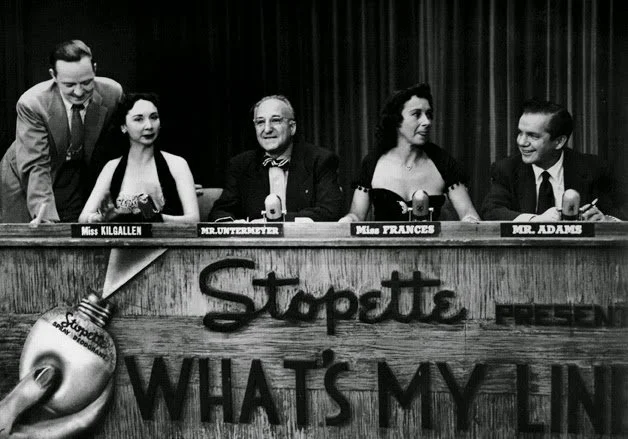

Among the original panelists was Louis Untermeyer, an unexpected television personality. Born on October 1st 1885, he was not an actor or media star but a renowned poet, literary critic and anthologist— a champion of American contemporaries like Robert Frost and contributor to influential literary magazines. He was known for his love of wordplay and conversational charm. Joining him on the charter panel was journalist Dorothy Kilgallen. Other guest panelists rotated in, and soon after actress Arlene Francis and comedian Hal Block arrived to form the show’s first regular quartet.

On the air, Untermeyer’s demeanor was polite and mild, a bit less showy than the others. By some accounts he lacked the quick ad-lib humor that a live game show required. Still, viewers enjoyed the balance he provided. His cultivated presence complemented Kilgallen’s journalistic shrewdness, Francis’s warmth and Block’s controversial antics. Together, they personified a New York “cocktail party” of sorts on the CBS stage.

Formality was a big part of What’s My Line? early on. The host, panelists and guests were often addressed by their surnames and donned business suits and street dresses.

But while What’s My Line? was providing light-hearted Sunday night entertainment, a far more serious drama was unfolding in American public life: the second “Red Scare.” The postwar anti-communist fervor— often called McCarthyism today— cast suspicion on countless individuals in government, education, Hollywood and broadcasting for any past left-wing associations. Unfortunately, Louis Untermeyer, despite his avowed patriotism and mainstream stature, quickly became a target. He had been an editor for Marxist publication The Masses during the first World War, and later wrote for the socialist journal, The New Masses. He was co-founder of the liberal arts magazine The Seven Arts, had joined antiracist and pacifist organizations, and in the the 1930s he briefly participated in the League of American Writers— a group later identified by authorities as a “Communist front.” By the end of World War II, Untermeyer’s socialist leanings had long since mellowed, he was more of a New Deal liberal and pacifist than a revolutionary. To hardline Red-hunters though, any history of activism was enough to trigger alarms.

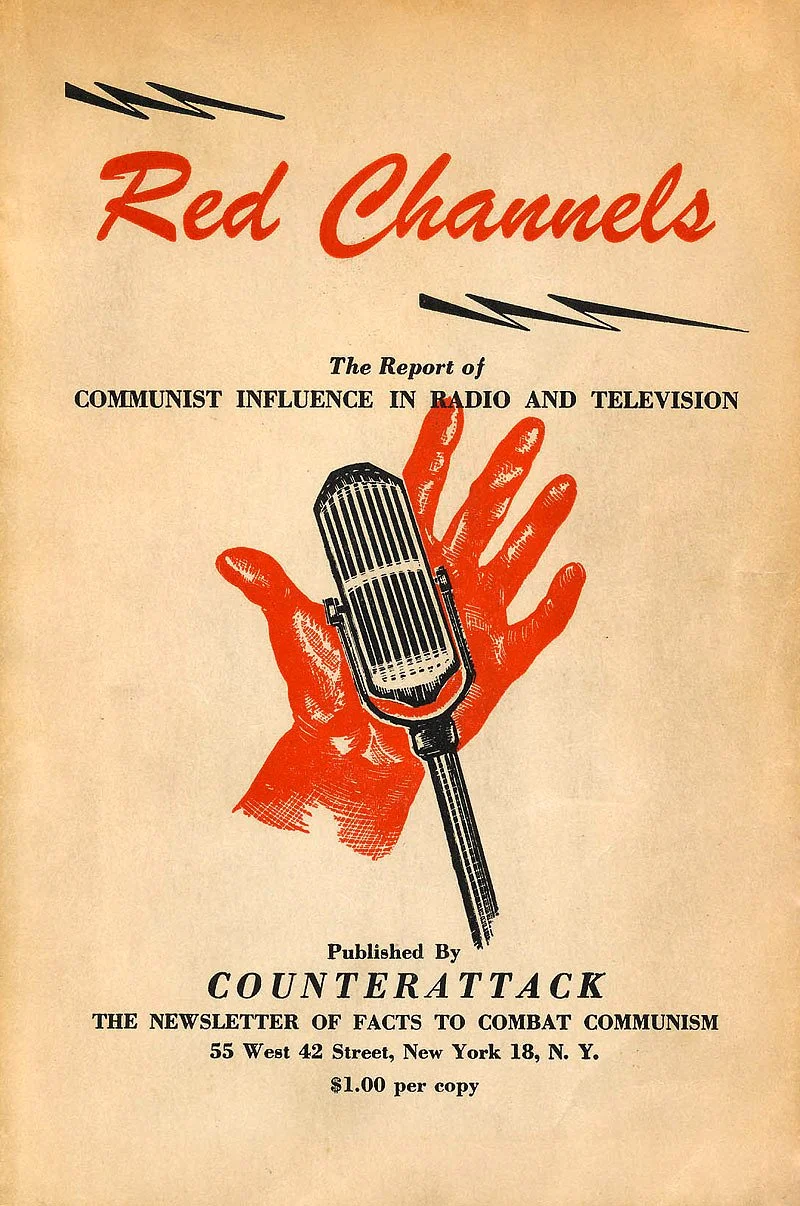

The flashpoint came with the publication of Red Channels in June 1950. This notorious pamphlet, subtitled “The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television,” was complied by a group of ex-FBI agents and private investigators bent on exposing purported subversives in the entertainment industry. Red Channels listed 151 names— actors, writers, musicians, etc.— along with their alleged Communist or leftist affiliations. Louis Untermeyer was one of them. Publisher and pundit Bennett Cerf, a future panelist on What’s My Line?, later quipped in his defense, he was “no more a Communist than J. Edgar Hoover”— he had merely “signed a few things too many” in his well-meaning eagerness to champion social justice or peace.

Red Channels was issued by the Newsletter Counterattack, which had been founded in 1947 by three ex-FBI agents working out of a small New York office.

By late 1950 though, Untermeyer was already a liability in the eyes of network executives and sponsors. What’s My Line? was a high-profile program, and CBS and its advertisers had been receiving complaints since the moment Red Channel’s hit the newsstands. Right-wing pressure groups mobilized. One particularly vocal organization was the Catholic War Veterans, which began to harass CBS with demands that Untermeyer be fired. Other patriotic societies joined the fray. They all painted the poet as a dangerous “Red” influencing American homes through the TV screen.

For a while, the team stood by their panelist. As Mark Goodson recalled years later, he was “very unhappy” about the pressure to drop Untermeyer. That autumn, he continued to appear on the show as usual, even as ominous clouds gathered overhead. However, the situation escalated rapidly. By early 1951, protestors took to the streets. Picketers began standing outside the New York studio of What’s My Line? on broadcasting nights, carrying signs denouncing Untermeyer’s alleged Communist ties. This unprecedented spectacle put CBS in a public relations bind. Sponsor Dr. Julius Montenier, whose company manufactured Stopette deodorant, soon delivered an ultimatum. According to Bennett Cerf, he said, “After all, I’m paying a lot of money for this. I can’t afford to have my product picketed.” In other words, if Louis Untermeyer remained on the show, Stopette would pull its sponsorship— a potentially fatal blow to the young program. The realities of commercial television meant that no controversy, however unjust, could be allowed to jeopardize advertising revenue.

That March, the mounting pressure reached its inevitable conclusion. Goodson and his partner Todman reluctantly informed Untermeyer that he was being removed from the panel “for the good of the show.” No public explanation was given. His final appearance was the live broadcast on March 11th 1951. That night the mystery guest was actress Celeste Holm, whom Untermeyer gamely questioned while blindfolded. Eight days later, Bennett Cerf appeared as a panelist and was soon introduced as a permeant fixture. Cerf— friendly, jocular, and politically uncontroversial— was exactly the kind of acceptable character the sponsor and network could embrace.

Bennett Cerf (second from the left) replaced Untermeyer on the panel in 1951 and remained on the show until its final episode in 1967.

For Untermeyer himself, the expulsion was devastating. At 65-years old, he had been caught entirely off-guard by the ferocity of the Red Scare. Playwright Arthur Miller— a friend and neighbor in New York— later described how he retreated from the world for a time. “An overwhelming and paralyzing fear had risen in him,” he said. Whenever Miller called to check on Untermeyer, his wife Bryna would answer the phone and give vague excuses, saying he “did not want phone conversations anymore.” The shame and anxiety of being effectively unemployable in his new medium— crushed the man’s spirit. As Miller observed, it wasn’t just political fear, but a personal sense of betrayal that haunted him. Moved by the ordeal, and similar stories of his associations “thrown into the street,” Arthur Miller penned a parable of persecution, The Crucible, unveiled in 1953.

Mark Goodson, the co-creator of What’s My Line?, was also needled by what occurred. To quell his regret, he quietly assisted other blacklisted performers on their quest for work. For example, he helped humorist Henry Morgan keep his job on I’ve Got A Secret, despite his name appearing in Red Channels.

Untermeyer eventually recovered from his depression and reclaimed his life outside the world of television. He left New York and bought a farmhouse in Connecticut. In time, his resilience and reputation rehabilitated his public standing. The virulence of McCarthyism ebbed by the mid-1950s, and Untermeyer’s peers never truly ceased respecting him. In 1956, the Poetry Society of America awarded him a gold medal for his contributions to the medium and in 1961— a decade after his TV ouster— President John F. Kennedy named him as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (essentially the nation’s Poet Laureate). This appointment, urged by Robert Frost, demonstrated that whatever stigma the Red Scare had attached to Untermeyer did not taint his literary legacy. He continued working almost up until his death in 1977, authoring or editing nearly one hundred books over the full scope of his career.

Citations

Barron, N. (2019, March 14). Louis Untermeyer: TV star to blacklisted celebrity. Bidwell Hollow. Retrieved from https://bidwellhollow.substack.com/p/louis-untermeyer-tv-star-to-blacklisted

Counterattack. (1950). Red channels: The report of Communist influence in radio and television. New York: Counterattack.

John T. (2025, March 26). The Living Mystery Guests of What’s My Line. The Many Rantings of John. Retrieved from http://theworldofjot29.blogspot.com/2025/03/the-living-mystery-guests-of-whats-my.html