BTS: Don’t Bother to Knock

Darryl F. Zanuck— production chief for 20th Century Fox— was virtually matchless when it came to underestimating the appeal of rising star Marilyn Monroe in 1951. Even as a staggering torrent of fan letters began to swamp the studio’s mailbox, practically on a daily basis, he remained adamant she was little more than a photogenic model, and a dim-witted one at that. Powerful beyond measure in the industry at the time, failing to draw his attention could and often did result in the end of many actress’s careers. But there’s always a bigger fish, and back then that fish was Joseph Schenck, elderly cofounder of Fox and one of its most influential board members.

“He simply could not bring himself to fully respect her as an actress or a woman. From Monroe’s point of view,” writer Scott Eyman explains in his book 20th Century Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio, “her past history with Zanuck and Schenck only made her more conscious of their lack of respect towards her, producing a toxic combination of insecurity and anger.”

-

Nebraska accented, cigar chomping Darryl Zanuck, once a lowly screenwriter at Warner Bros, had been in charge of production at 20th Century Fox since 1935. “He pursued a hands on approach to every project underway at the studio,” wrote Foster Hirsch in his book Hollywood and the Movies of the Fifties, “offering advice whether solicited or not, about scripting, casting, and editing.” Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Wilson (1944), Gentleman’s Agreement and The Snake Pit (both 1948), Pinky (1949), All About Eve and No Way Out (both 1950) were just a handful of the highly-regarded films released during his tenure. Zanuck already had three Best Picture wins under his belt by 1951 (for How Green Was My Valley (1941), Gentlemen’s and Eve), and a plethora of nominations for the prestigious award otherwise, dating back to Disraeli, a 1929 historical film he had produced about the life of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.

On a much uglier note however, in a 2017 article penned by Nick Schager (an entertainment critic for The Daily Beast)— Zanuck is credited alongside fellow movie mogul Harry “White Fang” Cohn (Columbia Pictures cofounder and production head from 1919 to 1958) as the originators of the industry’s notorious “casting coach”. Variety writer Thelma Adams, in an article also released in 2017 (both were responses to allegations regarding Harvey Weinstein, which had just broke), quotes Marilyn Monroe’s memoir My Story. “I met them all. Phoniness and failure were all over them. Some were vicious and crooked. But they were as near to movies as you could get. So you sat with them, listening to their lies and schemes. And you saw Hollywood with their eyes— an overcrowded brothel, a merry-go-round with beds for horses.” Zanuck, according to Schager, held “conferences” with actresses “every afternoon from 4-4:30 p.m.”

In 1951, while vacationing on the French Riviera, Zanuck and his wife Virginia met Bejla Węgier, a bisexual Polish-Jew and compulsive gambler who had survived captivity in a concentration camp during World War II. Alexander D’Arcy, a friend of Virginia’s, had introduced her to them. She soon became intimate with Zanuck and was invited to live in an annex attached to his house in Santa Monica the following year. He also paid off her gambling debts and groomed her for stardom under the name Bella Darvi (a bizarre combo of his and his wife’s first names). Rumors spread that she was, in some capacity, involved with Virginia as well— although this is perhaps unlikely if reports regarding the the latter becoming aware of her husband’s relationship with Węgier and kicking the woman off the property in 1954 are to be believed.

Schenck had taken a fierce, personal interest in Monroe’s future… for some reason. Rumors had been flying around the office that they were involved. Those rumors were correct, their relationship was fairly complex. But in any case, he demanded she be cast as the lead in an upcoming thriller based on Mischief, a novel by Charlotte Armstrong. Fox’s president, Spyros Skouras, was also in Monroe’s corner. Together, they pressured Zanuck to turn the project into her first star vehicle.

Zanuck countered pragmatically, insisting she prove her ability with a screen test first. If she failed, he’d have the justification he needed to give the job to someone else. If she passed, at least he could say he’d ensured she was up to the challenge.

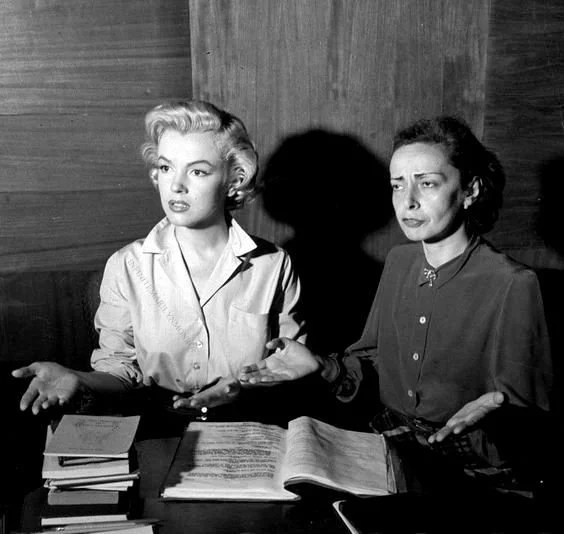

Monroe, assisted by her acting coach Natasha Lytess, prepared with near-pathological dedication. Reportedly, she stayed awake for forty-eight hours straight, attempting to summon the dizzy, wide-eyed energy required for the part. The outcome was as raw and intense as she’d hoped it would be. Left with no other choice, Zanuck begrudgingly green-lit the movie.

-

On June 1, 1926 in Los Angeles, California, Norma Jeane Mortenson— better known to the world as Marilyn Monroe— was born. The child of Gladys Baker, an impoverished woman struggling with mental illness, she spent most of her childhood in foster care. At sixteen, in 1942, desperate to avoid another stint at the Los Angeles Orphans Home, she married her former neighbor, James Dougherty. Two years later, with the nation engulfed in World War II, she took a job on an assembly line in a munitions factory while he served overseas as a Merchant Marine in the Republic of China. Spotted by an Army photographer, she began modeling— making her first appearance in Yank magazine. In 1946, she divorced Dougherty (who disapproved of her new career) and signed a contract with 20th Century-Fox, adopting her famous stage name.

Dropped after a year but still relentless, she turned to the “party circuit.” At one gathering, she met Pat De Cicco— an associate of Joseph Schenck, the immensely wealthy cofounder of Fox— and received an invitation to one of Schenck’s all-night Saturday card games in Holmby Hills, a coveted fixture of the Hollywood social scene. For a time, Monroe was “Schenck’s girl.” As biographer Barbara Leaming recounts, she lived in his guest cottage, served drinks, and emptied ashtrays. Pleased, Schenck eventually persuaded Columbia’s Harry Cohn to sign her, although the studio gave her little to do. After a brief flirtation with vocal coach Fred Karger ran its course, her fortunes shifted in 1950 when Johnny Hyde— a sickly, physically diminutive but influential William Morris talent agent—decided to champion her.

They met at a New Year’s Eve party on North Crescent Drive in Beverly Hills, hosted by producer Sam Spiegel on December 31, 1948. According to Leaming, Monroe had “established herself as one of the producer’s ‘house girls’”— prostitutes and ambitious starlets who catered to Spiegel’s powerful friends. Hyde, amid turmoil involving his client Rita Hayworth, noticed Monroe perched on a barstool and became instantly infatuated. He whisked her away to Palm Springs and began speaking of her everywhere he went. Hoping to marry her, Hyde left his wife and children. Monroe, however, saw him as a father figure (she never knew her own father) and believed marrying for money would prevent her from ever earning the respect she so desired from her contemporaries. Even so, Hyde secured for the actress small but pivotal roles in The Asphalt Jungle and All About Eve that earned her significant critical accolades that year. Then, in December, tragedy struck. While recuperating in Palm Springs from recent chest pains, Hyde died of a heart attack. Monroe had been Christmas shopping in Tijuana with her acting coach, Natasha Lytess, when it happened.

Just a week earlier, Hyde had finally succeeded in getting Monroe back under contract at 20th Century-Fox. His death, however, blunted that victory. The William Morris Agency let the contract paperwork sit untouched for three weeks—an unmistakable sign of apathy. Darryl F. Zanuck, the studio’s head of production, despised her and was not inclined to assign her decent roles or even pick up her contract once it expired, leaving her exactly where she had started. Grieving both Hyde and the future he had promised her, Monroe reported to the set of As Young As You Feel, a Harmon Jones comedy. It looked as if this bit part— as a secretary— would be the end of the road.

Sobbing alone on an empty soundstage, Monroe was suddenly approached by Elia Kazan, one of Hollywood’s most sought-after directors. He offered his condolences. They had, in fact, met twice before through Hyde. Accompanied by his playwright friend Arthur Miller— both men were New Yorkers— Kazan had come to town hoping to sell Miller’s new script, The Hook, a tale of waterfront union corruption. She had also heard Kazan was casting Viva Zapata!, a film about Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. In him, Monroe saw opportunity. He invited her to dinner. She said yes.

-

Soon after their meeting on the set of Harmon Jones’s picture, Marilyn Monroe and Elia Kazan (who was married with children) began an affair. At first, they spent long nights in her hotel room at the Beverly-Carlton on West Olympic. When a newly purchased baby-grand piano cramped the room, they migrated to lavish home of agent-producer Charles Feldman— who was away on business, and had lent the residence to Kazan and Arthur Miller. Feldman was also producing A Streetcar Named Desire, a Tennessee Williams adaption directed by Kazan. His home was elaborately decorated— expensive art hung on the walls, there was a heated pool and a garden, Chinese stone heads, animal sculptures and Buddhas from Thailand. Down the hall, Miller hammered out drafts of The Hook on his typewriter. Darryl Zanuck had already turned it down, not because of the quality of the screenplay (although Kazan had made his dissatisfaction with it known) but due to its politically sensitive subject matter. Kazan’s agent Abe Lastfogel, who Monroe knew as Johnny Hyde’s partner at William Morris, received a similar response from Warner Bros.

Monroe became, according to Barbara Leaming, their “mascot”, tagging along when the men pitched their project to Harry Cohn. As a practical joke, they introduced her as “Miss. Bauer”, Kazan’s secretary. Days later, on January 21st, Charles Feldman returned from New York and set up a dinner party in Miller’s honor. Kazan, on a date with another girl, passed Monroe off to Miller at the last minute. Monroe tried to turn the playwright down— aware she had been essentially discarded— but Miller insisted she allow him to take her. They hit it off, a fact noticed by Kazan when he arrived late, his date having fell through. “Miller,” according to Leaming, “made no move to sleep with her, though he desired her very much. Marilyn, accustomed to being pawed by men, interpreted his shyness and awkwardness as a sign of respect.”

For weeks, the trio of Monroe, Kazan and Miller had been touring Hollywood. They’d lunched, drove through the canyons, shopped and browsed bookstores. Although both married, Miller and Kazan were not of the same temperament. Nervous about where his growing feelings towards Monroe might lead him, Miller fled the day after Feldman’s party. Later, he recalled, “When we parted, I kissed her cheek and she sucked in a surprised breath. I started to laugh at her overacting until the solemnity of feeling in her eyes shocked me into remorse…” I had to escape her childish voracity… her scent still on my hands…”

While their relationship had technically remained platonic in 1951, they struggled to forget each other once he was back in New York. In one letter, she told him, “Most people can admire their fathers, but I never had one. I need someone to admire.” “If you need someone to admire,” he replied, “why not Abraham Lincoln?” Monroe purchased a portrait and a biography by Carl Sanburg. She also apparently kept a copy of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. As noted by The Marilyn Monroe Collection, she came to identify Miller with the late-president— seeing them as honorable, intelligent men committed to their principles.

Meanwhile, Monroe was still fixed on the idea of convincing Kazan to cast her in a film. Perhaps believing that the director would only remain interested if she could drum up some kind of competition, she talked about Miller constantly. During their nightly sexual excursions, Kazan noticed a black-and-white photo of his friend, leaning against some books on a low shelf over the satin comforter in her hotel room. The men had an intense association, she knew— stemming from Kazan’s tendency to shift his favor at random, pitting Miller against his primary rival in the world of Broadway— Tennessee Williams. Preceding their trip to LA, Kazan had decided not to work on Williams’s Rose Tattoo, the inverse of his decision prior to that— in which he opted to direct Williams’s Streetcar over a film version of Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

But storm clouds, out of Monroe’s control, began to gather overhead. From about 1934 to 1936, Kazan had been a member of the Communist Party (CPUSA)— and given new life by the U.S.’s involvement in the Korea War, the House Un-American Activities Committee had been searching high-and-low for subversives in the film industry. Kazan knew he could be summoned to testify at any moment. “He was visible. He was successful. He was very much in demand. Those qualities,” Leaming explains in Marilyn Monroe, “made him a prime target for a committee whose raison d’etre, in large part, was publicity.” “It may be,” the biographer postulates, “that Kazan, accustomed as he was to being master of his own fate, had arrived in Hollywood with a politically provocative script like The Hook as a way of taking charge, of deliberately causing a subpoena to be issued.”

Since their meeting, Harry Cohn had turned The Hook over to Roy Brewer, head of Hollywood’s stagehands union. Joe Ryan, leader of the International Longshoreman’s Association, was a close friend of his. Brewer got back to Cohn quickly, informing the executive that he had asked the FBI to read Miller’s script and they were extremely alarmed by its content. Brewer demanded the film’s villains be defined as Communists and that the dominant theme be changed to that of “anti-communism”. If not, he threatened to call for a projectionist walk-out of every theater that screened it. Instead of adhering to Brewer’s request, Arthur Miller announced he would be scrapping The Hook. When she heard, Monroe was enthralled by his bravery.

After about six weeks in Los Angeles, Elia Kazan had had enough. He made necessary arraignments for Viva Zapata!, which he would begin shooting at the end of May. Then, he booked a flight home to New York for February 23rd. The next time he was in town, he’d be accompanied by his wife, Molly, and their children. Monroe knew she would not be able to interact with him very much at that point, and panicked. He had still not offered her a role, so she rolled the dice— and told him that she was pregnant. When pure horror crossed his face, she quickly told him not to worry. She wrote him later, claiming she’d miscarried. “It scared the hell out of me. I knew she dearly wanted a child… Like any other louse,” Kazan said, according to Donald Spoto, “I decided to call a halt in my carrying on, a resolve that didn’t last long.”

-

On March 29th 1951, Marilyn Monroe attended the 23rd Academy Awards for the first and only time. All About Eve, in which she had played a small part, earned fourteen nominations that year and she had been asked to present Best Sound Recording. According to a VOGUE article written by Hayley Maitland, there were 1,800 attendees at the Pantages Theatre that day, located at 6233 Hollywood Boulevard (roughly a half hour away from the hotel she had been living in at the time). Mayor Mogens Skot-Hansen of Los Angeles and Governor Earl Warren of California were in the audience, and the host was Fred Astaire.

In Maitland’s account of the night, Monroe chose a gown from Fox’s costume department (most stars of the era did the same, from their own studios). Her’s had been made by Charles LeMaire, who had been awarded, along with Edith Head, Best Costume Design for All About Eve. Just before going on, Monroe became upset when she noticed a rip in her dress and refused to go on stage. A seamstress arrived to solve the problem and before long, Monroe headed out to make her speech. The award she presented was also ultimately won by All About Eve— which had been up against Disney’s Cinderella, among others.

Fred Astaire, introducing her, made reference to a recent photoshoot she had participated in with the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball team. It’s unclear why he mentioned this team, but as an article on The Marilyn Report concludes, “he may have been referring to another baseball team, the Chicago White Sox, whom she had met less than three weeks before.” Noted in the same piece, this photoshoot is what caught the eye of Joe DiMaggio— who began pursuing Monroe almost a full year later.

Zanuck may have refused to drown the production in cash and fanfare (he allocated about $2 million), but he wasn’t particularly interested in sabotaging it either. He assigned solid professionals and simply demanded they adhere to a tight schedule. Daniel Taradash, who would win an Oscar in 1953 for From Here to Eternity, wrote the screenplay. Veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballard was hired to shoot it and respected composer Alfred Newman oversaw the score. Producer Julian Blaustein made sure any requests from Zanuck were actioned promptly and the entire story was filmed on the studio lot— where regulars quickly constructed a credible hotel setting.

Finally, directing duties fell to Roy Ward Baker. An Englishman in his mid-thirties, he had sharpened his skills in the British film industry, working initially on wartime documentaries and later feature films. Recently contracted by Fox, Don’t Bother to Knock would be his first wholly American-made picture.

Morning Departure, a tense submarine drama helmed by Roy Ward Baker and starring John Mills, caught Zanuck’s attention in 1950. Always on the hunt for new talent, the mogul brought Baker over to Fox on a three year contract. His first assignment was The House in the Square, a period fantasy shot in the U.K. starring Tyrone Power.

Like Zanuck, Baker harbored serious misgivings about the casting of Marilyn Monroe. He thought her too physically mature to play a frail, mentally-ill babysitter, and furthermore, he saw her as generally inexperienced. Interviewed decades later, he would reveal that, despite his feelings he understood that DBTK could have been something akin to a last chance for her. He noted that, at the time, she had been in about fifteen motion pictures without really “breaking out,” in a traditional sense. So, if this opportunity failed to garner significant accolades, her career could have run its course then and there.

With the wardrobe department, Baker met with his leading lady for the first time to brainstorm her look. Billy Travilla, a costume designer and friend of Monroe’s, was also in attendance. Collectively, they decided to dial down her trademark glamour for the role. “We made her look as plain as possible,” Baker recalled, “all of which made her look, if anything, more attractive.”

-

The contract with 20th Century Fox that talent agent Johnny Hyde had helped Marilyn Monroe land in December 1950, just before his death, only lasted six months— and his colleagues at William Morris weren’t responsive to her requests for their assistance— Susan Doll recounts in an article on howstuffworks.com. “She called her former agent, Harry Lipton, for advice,” Doll goes on, “and he suggested that she see Hugh French at the Famous Artists Agency.”

While French agreed to help her extend her contract with Fox, it was Monroe’s appearance at Fox’s exhibitors’ party during the spring of 1951 that sealed the deal. That March, Spyros Skouras had come to Los Angeles for the prestigious event, five days of screenings and a luncheon at the studio commissary. Celebrities like Tyrone Power, Susan Hayward and Anne Baxter were in attendance, as was Zanuck and Joseph Schenck. Skouras was the president of Fox, according to Barbara Leaming, but he preferred to remain in New York. He and Zanuck were known to be at odds with each other— the production chief almost never checked with Skouras on a script and only sent finished productions to the east coast for him to view.

Skouras was seated at the main table when Monroe entered the room, typically late. A reporter for Collier’s couldn’t help but compare her to Cinderella. She was in a strapless, black cocktail gown, determined to get the studio president’s attention. She’d heard from Johnny Hyde, according to Leaming, that the best way to get what you wanted at Fox was to pit Zanuck and Skouras against each other. Someone at another table asked her, “And what pictures are you going to be in, Miss. Monroe?” She replied carefully, “You’ll have to ask Mr. Skouras.” Skouras, who had seen All About Eve and The Asphalt Jungle asked Joseph Schenck the same question. Schenck told him she had no assignments and her contract was almost up for renewal. Skouras was astounded, and soon she was seated at the table next to him. He told her that not only was she going to remain at Fox, but that he would be ordering studio executives to find new projects for her posthaste.

As a byproduct of this incident, Charles Feldman (Hugh French’s colleague at Famous Artists) took an interest in her. Feldman had seen her, up until that point, as merely a sexual conquest. This image was reinforced by her nightly rendezvous with director Elia Kazan at his house the previous winter. However, things had changed by early May, when she and Kazan saw him for dinner— now, she’d earned herself a powerful ally at 20th Century Fox. Monroe had also, by then, just finished working on another comedy, Love Nest, and yet another, Let’s Make it Legal, would begin shooting in June. These were simple, fluff projects— but perhaps Feldman was starting to see something he hadn't before. He decided to keep an eye on her…

As the pieces started to fall into place that December, another individual made her presence known behind the scenes in a less official capacity. Natasha Lytess was Monroe’s German-born acting coach, the same one who had helped her vigorously prepare for Zanuck’s screen test. The duo had been associated since 1948, when the actress was still under contract at Columbia Pictures. Lytess had been the head drama instructor, and was assigned to work with Monroe that year on Ladies of the Chorus, a B-musical in which she had been given a small part. Hungry to learn and chronically insecure, Monroe latched onto her teachings. Their collaboration continued after Monroe’s contract lapsed, and within a few years Lytess had become far more than just a pedagogue to the ambitious bombshell. She was her confidante, quasi-therapist and all-around guru.

-

Wary of anti-German prejudice, Natasha Lytess often told people she was Russian, although in truth she was a native Berliner, born on May 16th, 1911. In his book, Donald Spoto tells us she “studied with the great director Max Reinhardt, acted in repertory theater, and married the novelist Bruno Frank.” Other sources are a little more skeptical about that last part. Fleeing their country as the Nazi’s took power, they “moved to Paris and thence to America, where they joined a throng of refugee artists, many of whom settled in Los Angeles. Reinhardt may have died of a heart attack in 1945 or returned to Germany in 1947, either way, Lytess was left to raise her young daughter, Barbara, on her own.

By this time, Lytess had transitioned from actor to acting coach, working with MGM and then Columbia Pictures in the late 1940s, where she met Marilyn Monroe. Actresses Mamie Van Doren, Virginia Leith and Ann Savage were also among those who received lessons from her over the years. “Natasha had aspired to a great stage career,” explains Spoto, “but in Los Angeles there had been only film work (and not much of that) and her accent and somewhat forbidding appearance limited available roles. As a result, her subsequent position as drama coach meant she had to abandon hopes for herself and work for the success of younger, more attractive and less talented actors.” Essentially, Natasha’s professional relationship with— and genuine affection for— Marilyn Monroe grew complicated due to her own nagging resentment of the up-and-coming starlet. “Marilyn was inhibited and cramped,” Spoto recalls her saying, “and she could not say a word freely.”

Throughout most of 1950, Monroe alternated between Johnny Hyde’s home at 718 North Palm Drive, Beverly Hills, and a modest room at the Beverly-Carlton on Olympic Boulevard, in order to avoid “press problems” stemming from Hyde’s decision to leave his family for her. That autumn, hoping to even further distance herself from potential scandal, she accepted an invitation from Lytess to cohabitate her apartment on Harper Avenue in West Hollywood. “There,” says Spoto, “Marilyn slept on a living room daybed, helped care for Natasha’s daughter Barbara, read books, studied plays and generally demolished Natasha’s neatness.” She was joined by Josefa, a chihuahua named after Joseph Schenck, who bought the dog for her twenty-fourth birthday. Unfortunately, Josefa “was never house-trained, there was excrement all over the place, and Marilyn could never face cleaning it up.”

In an article that can be found an howstuffworks.com, writer Susan Doll explains that after his death that December, Johnny Hyde’s wife and children evidently blamed Monroe for the destruction of their family and let her know through intermediaries that she was not welcome at his funeral. “Inconsolable”, she decided to attend anyway, encouraged by some of his associates to do so. According to Spoto, “Marilyn sat a long while at the cemetery, until, at twilight, attendants gently asked her to leave.”

Some time later, Lytess, who’d also attended the funeral, returned home to find a note from Monroe on her pillow:

“I leave my car and fur stole to Natasha.”

The stole had been a gift from Hyde— it was her most prized possession. Lytess found Monroe in the bedroom, unconscious after swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills from Schwab’s. Rushed to the hospital, where doctors pumped her stomach, the actress reportedly exclaimed, “Still alive. Damn. All those bastards.” This does not seem to have been her first attempt at suicide. In the mid-1940s, while her first husband was serving overseas, it is likely she used a similar tactic to try to end her life upon learning of an affair he’d had with his ex-girlfriend.

Monroe spent the rest of the year on the futon at Lytess’s place, attended night classes at UCLA— always self-conscious about her lack of schooling. In January, she moved back into the Beverly-Carlton Hotel, this time bunking with her friend and fellow actress, Shelley Winters.

Meanwhile, Lytess’s lease had expired. She planned to buy a small house, 611 North Crescent Drive in Beverly Hills, but “unaware of the complexities of mortgages and bank loans”, she ended up $1000 short. When Monroe found out, she immediately sold her mink stole and gave her all the proceeds. By winter 1951, they were living together once again. Monroe stayed there throughout the filming of Don’t Bother to Knock, departing at the end of production to reestablish her own residence in early 1952.

Baker was forewarned about Monroe’s dependency on her coach. Before production began, she made a formal request for access to the set on Lytess’s behalf. It ascended the chain of command until it reached Darryl Zanuck, who’s response was a firm and predictable, “no.”

One morning in late December 1950, Marilyn Monroe called Natasha Lytess and told her that she had just found out the name and location of her (Marilyn’s) father. Lytess agreed to travel with her to meet him. Together, they started towards Palm Springs and then into the desert where they stopped at a service station. Monroe stepped out to call ahead but returned with bad news— her father, according to biographer Donald Spoto, refused to see her. No name for this individual has ever been revealed, and it’s possible they may have never actually existed.

In a letter dated December 10th 1951, he called her request, “completely impractical and impossible.” Clearly referencing Lytess (though not by name), he warned, “You have built up a Svengali and if you are going to progress with your career and become as important talent-wise as you have publicity-wise then you must destroy this Svengali before it destroys you.” He concluded by reminding her that she had been cast “as an individual,” implying that her own instincts— not Natasha Lytess’s— were what the studio expected her to rely on.

Monroe, of course, brought Lytess to work anyway. Baker generously tolerated her inclusion as long as she stayed out of the way. But inevitably her influence started to seep in. Monroe turned to her every time Baker yelled “cut,” looking for approval. If she frowned or shook her head, the actress would fall apart and beg for a do-over. The breaking point came during a take in which she delivered a line of dialogue in a way that struck him as odd. Suddenly, Baker realized that she was imitating a heavy German-accent— channeling Lytess instead of the character she was meant to portray. At once, he decided to banish her from the set for good.

Lytess didn’t quite disappear. She continued to work with Monroe every night and Monroe found ways to contact her discreetly during the day. In any event, as the weeks rolled on, through the holidays and into January 1952, the cast and crew held their breath, hoping she could still solider-on under the director’s new conditions.

In the months leading up to her role in DBTK, Lytess introduced Marilyn Monroe to acting coach Michael Chekhov, and she began attending his classes. Chekhov was the nephew of Anton Chekhov, a Russian playwright and an associate of Konstantin Stanislavsky. His book, Actor: On the Technique of Acting, was one of Monroe’s favorites. In the words of Donald Spoto, “he was the kindliest mentor-father in her life thus far, and still another of Marilyn’s connections to the Russian tradition so prized by the Actors Lab and Natasha.” The Actors Lab he referred too was an LA acting school that would play an important role in Monroe’s life during the mid-1950s.

-

What Johnny Hyde set-up by getting Marilyn Monroe cast in All About Eve and The Asphalt Jungle, Sidney Skolsky spiked over the net by campaigning for her inclusion in Clash By Night in late 1951. He was a classic Hollywood eccentric, around five-feet tall, and worked as an entertainment journalist. His office was on the mezzanine outside Schwab’s Drugstore at 9024 Sunset Boulevard. “Hypochondriacal, fearful of everything from dogs and cats to swimming,” writes Donald Spoto, “Skolsky also suffered from mysterious depressions.” Recalling Monroe, his daughter, Steffi Sidney Splaver once said, “They were both like frightened puppies, both brighter than they knew, and of course Marilyn had a weakness for fatherly, intellectual Jewish men.” Spoto also explains the drug store connection in his book, “Schwab’s provided their pill-addicted tenant with whatever compounds he required or wished to sample. Throughout the 1950s, drugs later known to be perilously habit forming were far more readily available than subsequently, there was no stigma attached to continual use, nor was there (as subsequently) strict government regulation on dangerous barbiturates, amphetamines and narcotics.”

Skolsky and Monroe were fast friends. They’d met on the 20th Century Fox lot where the reporter procured free haircuts and mingled with stars and staff. By all accounts, it was a rare non-sexual relationship for her too— they seem to have been genuine platonic companions. According to a letter of acknowledgment to him from thankful producer Jerry Wald, cited by Spoto, it was Skolsky’s vigorous campaigning on Monroe’s behalf alone that led to her inclusion in RKO’s Clash By Night, filmed during the fall of 1951. Wald had met with Marilyn at Lucy’s on Melrose Boulevard and was fascinated by her youthful appearance (he wanted a younger actress to lure in teen audiences according to blogger Gary-Vitacco-Robles) He called Lew Schreiber at Fox and requested a loan of the actress for a six-week shoot. Schreiber asked for only three thousand dollars, a startlingly cheap amount for a transaction of that type. The film was an adaptation of a 1941 neo-realist play by Clifford Odets, the story of an unhappily married woman in the midst of an affair— set in Monterey, California. Peggy, Monroe’s character, works as a sardine packer and is engaged to the main character’s brother.

Monroe was anxious and physically sick at points during the production, and even broke out in a rash. Natasha Lytess, her coach, accompanied her on set. Fritz Lang, a German immigrant and the legendary director behind Metropolis (1927) and M (1931), did not get along with either woman. “She was so nervous she missed many of her lines,” Natasha apparently said, “and then Lang took her on like a madman.” On the other hand, Barbara Stanwyck (the film’s lead actress), was patient and understanding when it came to her interactions with Monroe. Later, she recalled a certain “magic” exuding from her, obvious to everyone present— eventually. Seeking realism, following the techniques she’d learned over the last year from Michael Chekhov, Monroe rejected the costume jewelry provided by the wardrobe department and asked to borrow a diamond ring worn by a wardrobe attendant. At one point, she was even given a rare opportunity for intoxicated acting— grabbing a sandwich off a tray in-character at a wedding reception, and hurling it to the ground.

Reporters began to arrive on set, not looking to speak with Stanwyck or Robert Ryan (the male lead), but instead, they wanted Marilyn Monroe. “We want to talk to the girl with the big tits,” Lang heard them say on several occasions. Monroe didn’t appreciate their treatment of her career as a side-note compared to her looks, and her anxiety about her future once more bubbled to the surface. However, as a rough cut of Clash By Night made rounds, Fox’s front office actually took notice. Finally, after years of hard labor, she’d gotten their damn attention.

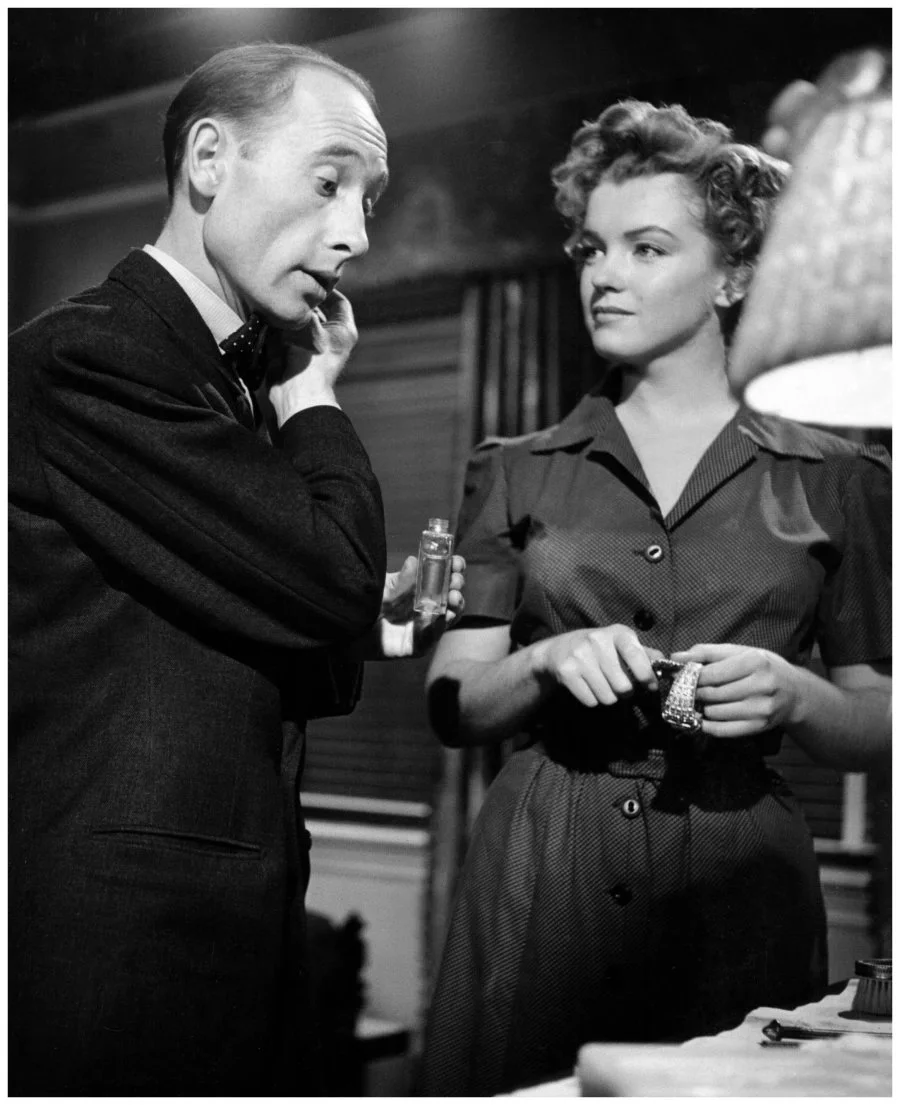

Monroe, as she was known to do often, arrived late— throwing off the timetable and frustrating co-star Richard Widmark. “We had to hell of a time getting her out of the dressing room,” he recollected. Once they did, she often appeared flustered or unprepared. She flubbed her lines, missed her cues, performed with little energy and then overcompensated with way too much. “She couldn’t act her way out of a paper bag,” Widmark said, “but she became an icon because something happened between her and the lens, and no one knows what it is.”

Anne Bancroft had very different perspective. Just as nervous as Monroe (Bancroft was starring in her debut role as lounge singer Lyn Lesley), she watched as her co-star openly battled her demons and learned from what she witnessed, rather than judged. Bancroft praised her performance when asked about the film years later, stating that in their crucial scene together— where Lyn confronts a distraught Nell (Monroe’s character) towards the end of the movie— Monroe’s authenticity caused a real emotional response from her. “It was a remarkable experience,” she said, “she moved me so tears came to my eyes.” Interestingly, according to her, Monroe disagreed with not just Baker’s opinion on how to play that scene, but also Natasha Lytess’s. If true, that would suggest Monroe actually did end up taking Zanuck’s advice, prioritizing her own instincts… at least once.

At the end of the day, Baker’s primary directorial challenge was molding something coherent out of her erratic process in the editing room. He’d exercised great patience, blowing through ten or fifteen takes by some accounts, hoping to cobble the usable bits together into a fluent whole. In time, behind the scenes accounts would suggest the exact opposite occurred, that Baker only needed one or two takes at most— bucking the usual narrative that Monroe was difficult to work with. Whatever the truth may have been, Don’t Bother to Knock was released during the summer of 1952 on that cautiously optimistic note. Baker had weathered the storm, Monroe could breathe a sigh of relief and Darryl Zanuck got the film he wanted, on time and under budget, with hopefully enough flair to recoup its cost. Thankfully, it did indeed (although just barely).

Despite the mixed reviews it received, the picture circulated in theaters alongside two others featuring Marilyn Monroe. Cultural saturation, boosted by a famously tumultuous relationship with retired Yankees megastar Joe DiMaggio that’d kicked off the previous March— made her a household name, and defined the final decade of her tragically brief life.

Citations

Leaming, Barbara. Marilyn Monroe. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998; New York: Three Rivers Press, 2000 (pbk.). Bibliographic record(s): WorldCat.

Spoto, Donald. Marilyn Monroe: The Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1993 (1st ed.). Bibliographic record(s): WorldCat (U.S. ed.; 1993) and Chatto & Windus (U.K. ed.; 1993).

Doll, Susan "Marilyn Monroe's Early Career" 29 August 2007. HowStuffWorks.com. <https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/marilyn-monroe-early-career.htm

Spoto, Donald. “Tour Marilyn Monroe’s Apartment in the Beverly Carlton Hotel and Spanish-Style House in Los Angeles.” Architectural Digest, 14 Sept. 2016

Maitland, Hayley. “Marilyn Monroe’s Only Oscars Appearance Featured a Major Fashion Mishap.” British Vogue, 28 Feb. 2025

Eyman, Scott. 20th Century-Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio. First edition, Running Press, 2021.

The Marilyn Monroe Collection. TheMarilynMonroeCollection.com, https://themarilynmonroecollection.com.

Schager, Nick. “Hollywood’s Heinous ‘Casting Couch’ Culture That Enabled Harvey Weinstein.” The Daily Beast, 14 Oct. 2017, https://www.thedailybeast.com/hollywoods-heinous-casting-couch-culture-that-enabled-harvey-weinstein

Adams, Thelma. “Casting-Couch Tactics Plagued Hollywood Before Harvey Weinstein.” Variety, 17 Oct. 2017, https://variety.com/2017/film/features/casting-couch-hollywood-sexual-harassment-harvey-weinstein-1202589895

Vitacco-Robles, Gary. “Marilyn: Behind the Icon – Clash by Night.” Classic Movie Hub, 15 June 2020, https://www.classicmoviehub.com/blog/marilyn-behind-the-icon-clash-by-night/

Hirsch, Foster. Hollywood and the Movies of the Fifties: The Collapse of the Studio System, the Thrill of Cinerama, and the Invasion of the Ultimate Body Snatcher — Television. Knopf, 2023.

marina72. “All About Marilyn’s Oscar Gown Drama.” The Marilyn Report, 7 Mar. 2023, https://themarilynreport.com/2023/03/07/all-about-marilyns-oscar-gown-drama

“A History of Suicide Attempts.” Marilyn Forever, 30 Mar. 2014, https://marilyn4ever.wordpress.com/2014/03/30/a-history-of-suicide-attempts

Allen, Shannon. “A Double Life, Shelley Winters and Marilyn Monroe.” Vanguard of Hollywood, 13 Nov. 2020, updated 13 Feb. 2025, https://vanguardofhollywood.com/double-life-shelley-winters-marilyn-monroe

“Two Men and a Little Lady.” The Times, 2 Oct. 2003, https://www.thetimes.com/travel/destinations/north-america-travel/us-travel/california/two-men-and-a-little-lady-8pmtmq3k6rk

“Marilyn Monroe and Washington, D.C.” The Marilyn Monroe Collection, TheMarilynMonroeCollection.com, https://themarilynmonroecollection.com/marilyn-monroe-and-washington-dc