REVIEW: FIVE

The title card for FIVE, a post-apocalyptic drama released in 1951

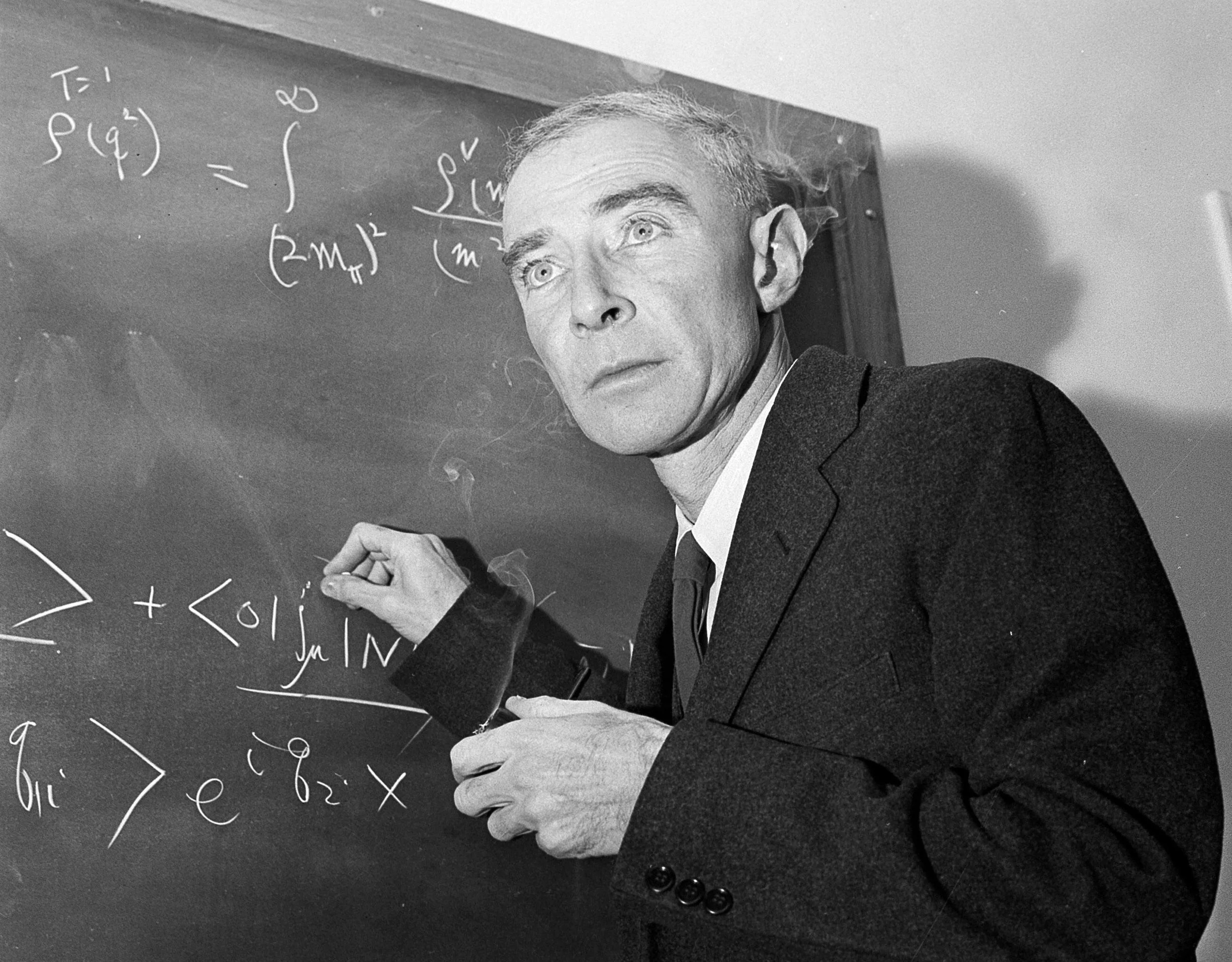

Days before Halloween 1946, American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer met with President Truman in the Oval Office for the first time. Their discussion, documented in a memo to then-Under Secretary of State Dean Acheson, was partially depicted in the 2023 film Oppenheimer.

Seated behind the Resolute desk— Truman asked the famed “father of the atomic bomb” how long it would take the Soviets to build their own weapons of mass destruction. Oppenheimer said that he didn't know. “I know,” Truman told him— according to David Halberstam’s book the Fifties. “When?” Oppenheimer inquired. “Never,” Truman chortled.

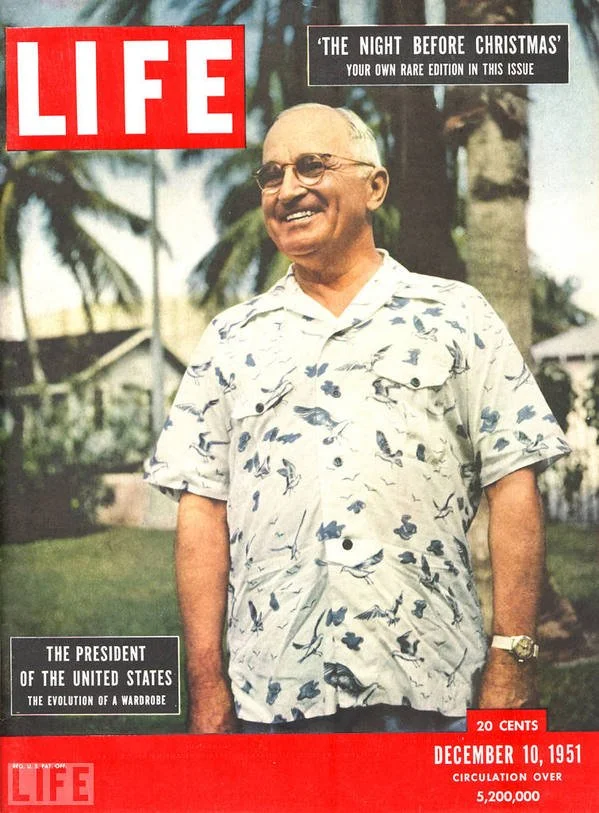

President Harry S. Truman on the cover of LIFE magazine, 1951

Some top scientists believed the Russians were five years behind the U.S. The CIA predicted they wouldn’t catch up until the mid-1950s, while the Army and Navy assumed the 1960s. All were proven wrong in early September 1949, when a long-range reconnaissance plane equipped for atmospheric sampling detected abnormally high levels of radioactivity over the North Pacific. Successive inquiries confirmed expert suspicions: the Russians had almost certainly set off an A-bomb at the end of August in or around the Kazakh SSR. Confronted weeks later, Truman was confounded. The American monopoly on nuclear weapons had officially ended. Overnight, the world dramatically changed.

J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904 - 1967)

Carefully constructed to avoid causing alarm, the president’s public announcement came on September 23rd 1949. The State Department, the Pentagon and the Atomic Energy Commission weighed their options— intense interagency discussions set against the Communist takeover of China, spy scares and a sharpening sense of Western vulnerability. By the beginning of 1950, arguments began to harden around accelerating work on the “Super”— a thermonuclear weapon of far greater destructive power than any previously developed.

Across the Western world, fear became practical. Federal printing presses rolled out Survival Under Atomic Attack, a slim booklet that attempted to educate layman on the effects of nuclear radiation and offered advice regarding sheltering, first-aid and decontamination. A chapter titled “Kill the Myths” conveyed “Atomic bombs hold more death and destruction than man ever before has wrapped up into a single package, but their over-all power still has very definite limits.”

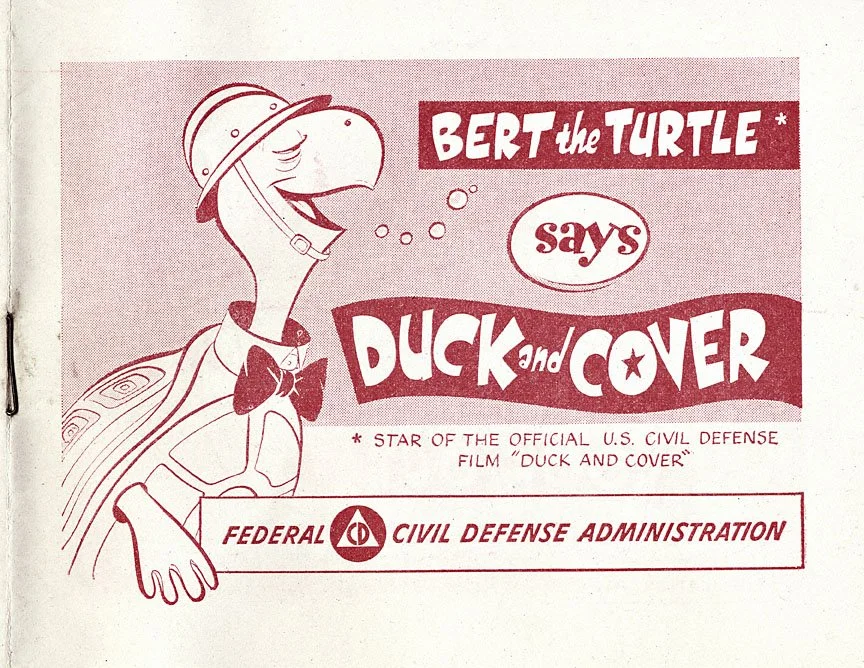

On January 12th, 1951, President Truman signed the Federal Civil Defense Act, formalizing the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) and thus creating a framework for coordinating state and public instruction. The FCDA’s most recognizable contribution, Duck and Cover starring an anthropomorphic turtle named Bert (produced by Archer Productions), entered classrooms on March 6th 1952. By the following April, nearly every elementary school kid in New York had been issued a dog tag with their name on it for identification, should death rain down from the sky. Children on the west coast, in places like Seattle, Las Vegas and San Francisco also received dog tags, and citizens both young and old in certain parts of Indiana and Utah were tattooed with their blood-type, meant to facilitate a kind of “walking blood bank.”

“Bert the Turtle” appeared in a number of cartoons, comic books and other publications during the 1950s as part of the FCDA’s propaganda campaign.

Enter Arch Oboler, a second-generation Latvian-American auteur who had become famous a little over a decade prior for his work on boundary-pushing radio plays like Lights Out. One abiding creation, a 1937 episode titled ‘The Chicken Heart,” immortalized in a bit by disgraced comedian Bill Cosby, followed efforts to contain a growing, scientifically altered chicken heart before it devours the earth. Throughout World War II, his output consisted of explicitly anti-fascist series like Plays for Americans. Turning his attention to the fears quickly engulfing the postwar age, Oboler produced, wrote and directed FIVE, a film widely considered the first to take place in a post-nuclear apocalypse.

Oboler kept the budget down ($75,000) by hiring a slim crew of several recent University of Southern California film school graduates, including Louis Clyde Stoumen (who would later win two Oscars for documentary work), and shooting the movie on his 360-acre compound off Mulholland Highway in the Santa Monica Mountains. Called “Eaglefeather,” two buildings on the property— referred to as “the Gatehouse” and “Cliff House”— were designed in the early 1940s by legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Their steep stairs, balconies and severe geometry granted the picture an almost otherworldly feel. The interiors too, strewn with scavenged props, lended much to Oboler’s haunting, empty-world aesthetic.

Eaglefeather, Oboler’s Santa Monica compound designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

The cast, mostly unknown actors, consisted of Susan Douglas Rubes, musician and Paul Robeson affiliate Charles Lampkin, Earl Lee, James Anderson (Bob Ewell in 1962’s To Kill a Mockingbird) and William Phipps (cast the previous year as the voice of Prince Charming in Disney’s Cinderella). Lee, nearing the end of his career, died in 1955. The plot concerns Rubes’s character— a pregnant woman named Roseanne— who joins a small group of survivors after a nuclear blast kills most of the world’s population. Together, amid squabbling and occasional violence, they attempt to rebuild a life for themselves out in the desert.

Arch Oboler (1907 - 1987)

Notably, the film largely rejects spectacle. No explosions appear on-screen and the camera meets the characters where they are, already amid the rubble. At one point Charles, played by Charles Lampkin, recites “The Creation,” a poem by James Weldon Johnson. This may have been the first time many Americans who saw the film were exposed to African-American poetry.

Even as an indie curiosity that opened without a seal of approval from the Production Code, FIVE was only a modest success. It premiered on April 25th 1951, distributed by Columbia (to whom Oboler sold all interest in the film to the following year). Critics were divided but most agreed the film was extremely slow and depressing. Yet, it proved historically significant— the starter pistol for a number of similarly themed movies like the Day the World Ended in 1955, On the Beach in 1959, Panic in Year Zero! in 1962, A Boy and His Dog in 1975— all the way up to Mad Max in 1979 and onward.

An overly talky, end-of-the-world chamber piece, FIVE is proof of what could be done outside the studio system, a system that was already beginning it’s death march since the 1947 court case United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. ended with a determination that studio ownership of movie theaters violated anti-trust laws. But that’s a little off topic, a story for another day. Far more important considering the concept of Oboler’s movie, was what happened on November 1st 1952, eighteen months after its release.

At Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands, the first true hydrogen bomb was detonated by a team from the United States. Named “Ivy Mike,” the yield was 10.4 megatons— over 700 times the power of the bomb that hit Hiroshima. The explosion vaporized an entire island, left a mile-wide crater in the sea… and lit up the sky like a second sun.

Citations

Halberstam, D. (1993). The fifties. New York, NY: Villard Books.

Hughes, J. (n.d.). “Duck and Cover” essay [PDF]. Library of Congress, National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-film-preservation-board/documents/duck_cover.pdf

Boaz, J. (2010, August 23). A Film Rumination: Five, Arch Oboler (1951). Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations. Retrieved from https://sciencefictionruminations.com/2010/08/23/a-film-rumination-five-arch-oboler-1951/

Crowther, B. (1951, April 26). The screen: Three films in local premieres — Five, Arch Oboler. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1951/04/26/archives/the-screen-three-films-in-local-premieres-five-arch-oboler.html