REVIEW: The Snake Pit

Academy Award winner Olivia de Havilland in The Snake Pit (1948)

In Anatole Litvak’s postwar psychological drama The Snake Pit, Virginia Cunningham (Olivia de Havilland) is a young, distressed writer that wakes up in an overcrowded asylum with no memory of how or why she got there. Flashbacks reveal her husband, Robert (Mark Stevens) had her committed after she suffered a nervous breakdown. Surrounded by deluded, screeching, zombie-like fellow patients and attendants who, for the most part, treat them quite poorly, she eventually finds solace under the guidance of Dr. Kik (Leo Genn), a pipe-smoking Freud-esche psychotherapist who helps her rediscover the truth about her past and regain her sanity. The picture’s blunt portrayal of the inhumane conditions endured by those locked-up in mental asylums (as many as 577,000 by 1950) shocked contemporary audiences in late 1948. It earned six nominations at the 21st Academy Awards, among them Best Actress for de Havilland, Best Director for Litvak and Best Picture, although it only won Best Sound Recording.

A Soviet expatriate since 1925, Anatole Litvak had directed a number of “message films” over the course of his career, frequently employing the use of gritty, film-noir aesthetics to drive his points home. One of his most frequent collaborators in the 1930s and 1940s was screenwriter John Wexley, who was named as a communist sympathizer in HUAC testimonies by director Edward Dmytryk in 1951, and by writers Robert Rossen and David Lang in 1953. Litvak himself was at the very least a leftist, which may explain the Sigmond Freud references— as noted by one modern critic in a review on columba.edu. Some socialists of the era saw Freud as a revolutionary who sought to defeat sexual repression like Marx sought to end economic repression. Either way, Freud was well-known by the American citizenry of the late 1940s, so his inclusion here, both abstractly in the form of Dr. Kik and more explicitly as a framed portrait in the doctor’s office, offers an interesting snapshot into his high-status among educated professionals during the postwar period.

While serving in the U.S. Army during WWII, Litvak became invested in psychiatric treatment, often encountering aquatinted soldiers suffering from what we would now call PTSD. When he came across a semi-autobiographical novel by author Mary Jane Ward— based on her own struggles with mental illness— he took it to 20th Century Fox’s powerful co-founder Darryl F. Zanuck to produce. Concurrently, Olivia de Havilland had established herself as one of the brightest stars in Hollywood. She had won an Oscar in 1946 for To Each His Own and achieved victory in a historic 1943 legal battle that freed her from a restrictive contract with Warner Bros. Her preference for playing complicated, outside-of-the-box characters drew her to Litvak’s project, and she embarked on several months of intensive research once she was hired.

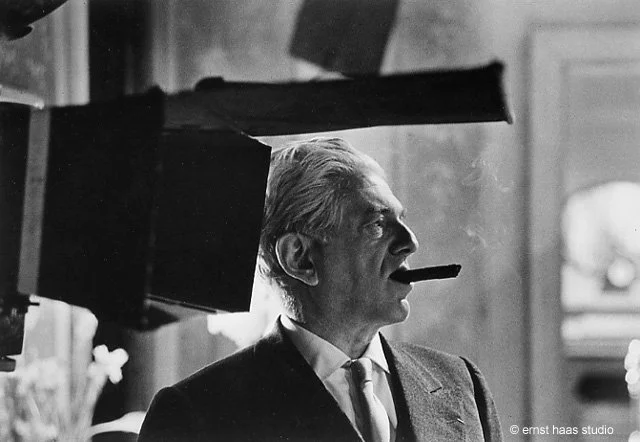

Anatole Mikhailovich Litvak (1902-1974)

Alongside the director and the rest of the cast (Genn, Stevens, Celeste Holm, etc.) de Havilland observed how the mental ill were cared for first hand. They visited hospitals, conducted interviews, assisted with electroshock therapy and attended patient social events. De Havilland also lost weight for the role to emulate the gaunt features of a sick woman. It was not the first time she had appeared on screen as someone struggling with their mental health either, The Dark Mirror was released in 1947. Her performance in The Snake Pit, an astounding balance of sadness, confusion and hope emanating from wide, unblinking eyes, solidified what fans and industry insiders already knew: de Havilland possessed unrivaled talent. She did not win the Best Actress award she was nominated for in 1949— but she did win it for The Heiress in 1950.

Anatole Litvak’s prestige grew considerably as well, the film netted an impressive $10 million on its $3.8 million budget. His next film, Decision Before Dawn, about German prisoners of war, was also nominated for Best Picture in 1952.

Amazing— yet still a product of its time, The Snake Pit reinforces messaging about the status of women in the 1940s (many modern critics have pointed out that Virginia is determined to be “cured” when she finally displays a willingness to return to her “proper role” as a wife and mother), while nobly advocating for the mentally ill. Claims have been made that over half the U.S. enacted state-wide health care reforms as a direct result of the movie. This is likely an exaggerated figure, but historians do seem to agree that it generated substantial awareness and certainly assisted in building the momentum necessary for improved conditions in the decades that followed.

Citations

“The Making of ‘The Snake Pit’ (1948).” Backlots. (2012, April 30). Retrieved from https://backlots.net/2012/04/30/the-making-of-the-snake-pit-1948/

“A Film to Remember: ‘The Snake Pit’ (1948).” Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/%40sadissinger/a-film-to-remember-the-snake-pit-1948-6f4704ec5095

“Olivia de Havilland in The Snake Pit (1948) – The Mental Kaleidoscope.” Pale Writer Blog. (2019). Retrieved from https://palewriter2.home.blog/2019/07/01/the-mental-kaleidoscope-olivia-de-havilland-in-the-snake-pit-1948/