REVIEW: Crossfire

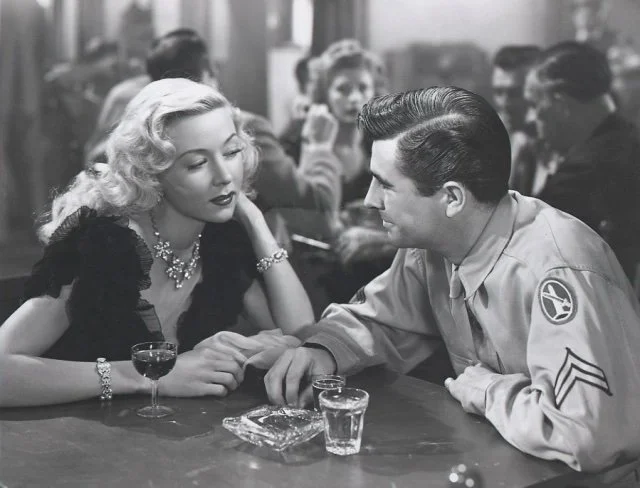

Gloria Grahame and George Cooper in Crossfire (1947)

Adapted from Richard Brook’s 1945 novel The Brick Foxhole— Crossfire (1947) began as a daring project intent on tackling lingering prejudice in post World War II America. The plot was uncomplicated: a Jewish man turns up dead and a group of off-duty solders find themselves implicated in his murder. Although the source material was about homophobia as opposed to anti-semitism, changes were made to satisfy the Hays Code (~1938-68), which banned references to homosexuality— considering it sexual perversion.

The movie was shot over a twenty day period on a modest budget of about $700,000 by director Edward Dmytryk, known for his efficiency and social conscientiousness. Producer Adrian Scott and screenwriter John Paxton had both worked with the director prior and shared his vision. They aimed to make the film’s anti-hate message as clear as possible, despite the constraints imposed. Crossfire also provides, for contemporary viewers, a fascinating look at gender roles, nebulous during this moment in American history as men, victorious overseas, struggled to re-acclimate to domestic society and women, who had stepped-up to take their place in the workforce, were encouraged to retreat into their traditional roles as housewives. To this point, the film’s antagonist (committed off-screen liberal Robert Ryan), notably directs his war-time aggression towards an innocent civilian. Meanwhile, the film’s lone unmarried female character, portrayed by the immaculate Gloria Grahame, lives a disillusioned existence on the margins of society.

RKO, the studio behind the picture, leveraged the popular appeal of three high-profile stars— the aforementioned Ryan and two other Roberts, Mitchum and Young— to reel in large audiences during the summer of 1947. Their gamble paid off; Crossfire was a critical success as well as a commercial one, earning more money for RKO than any other film that year (over $2 million) and five Oscar nominations including for Best Supporting Actor and Actress for Ryan and Grahame respectively, as well as Best Picture, the first “B movie” to do so. That coveted top prize however, was ultimately given to the filmmakers behind Gentlemen’s Agreement— a film by Elia Kazan starring Gregory Peck that also dealt with anti-semitism, released in the Fall.

Ironic considering the film’s coverage of one form of blind hatred, the team behind Crossfire soon fell victim to another as the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) soon swept into Hollywood seeking to uncover the truth behind swirling rumors of pro-communist subversion. Perhaps the most famous detail involving Crossfire, in October 1947, Edward Dmytryk and producer Scott were hauled into congress. Both refused to testify or “name names” and were cited in contempt as a result alongside eight of their colleagues referred to as the “Hollywood Ten.” Blacklisted by the industry and sentenced to prison, Dmytryk initially fled across the pond to England but returned to serve his time in 1951.

Cooperating with HUAC, he identified as communists twenty of his friends and associates, and was granted a chance to revive his career in the States. Adrian Scott, one of the twenty he named, never worked in Hollywood again unfortunately.

The House Un-American Activities Committee included Chairman J. Parnell Thomas (second from the left) and future president Richard Nixon (far right)

Gloria Grahame, a young actress at the time, was surprised by her nomination at the 20th Academy Awards and found her career surging after Crossfire. She was nominated again in 1953 and won for her role in The Bad and the Beautiful. Meanwhile, Robert Ryan’s nuanced performance set the stage for the intense, troubled characters that would quickly become his specialty. Robert Mitchum continued to excel as a noir-film leading man, his rough, enigmatic persona cemented by a highly publicized arrest for marijuana possession in 1948. Robert Young, by contrast, pivoted away from the big-screen, taking on the role of an idealized 1950s family-man in TVs Father Knows Best.

To put a bow on it, Crossfire is a fine, maybe exceptional film that, at the time of its release, suggested the undisputed truth of what Americans would soon experience first hand. Beneath the glossy, optimistic post-war atmosphere, lurked divisions and hatred that needed to confronted head-on. It’s a shame that didn’t happen, but it’s never too late. Our nation can still heal. It just takes a bit of effort from all of us to be kinder to each other, and faith that for every awful, hateful action committed against an unsuspecting, fellow human— there’s a good samaritan just around the corner, happy to extend their hand in solidarity.

Citations

“A Splash of Light in the Darkness: Edward Dmytryk’s Crossfire.” Senses of Cinema. (2024, March 7). Retrieved from https://sensesofcinema.com/2024/cteq/a-splash-of-light-in-the-darkness-edward-dmytryk’s-crossfire/

“146. Crossfire, 1947.” Jay’s Classic Movie Blog. (2024, February 20). Retrieved from https://www.jaysclassicmovieblog.com/post/crossfire-1947

“CROSSFIRE (1947).” Film Noir Board Blog. (2021, April 25). Retrieved from https://filmnoirboard.blogspot.com/2021/04/crossfire-1947.html