REVIEW: Don’t Bother to Knock

20th Century Fox’s production chief Darryl F. Zanuck was among Hollywood’s most powerful in the early 1950s. He was known for his hands-on management style and insatiable penchant for attractive, blonde starlets. Twenty-five-year-old Norma Jeane Mortenson— better known by her stage name, Marilyn Monroe— was one of them, although not one he favored.

Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962) backstage at the 23rd Academy Awards on March 29th 1951, she presented the award for Best Sound Recording.

Despite the immense amount of fan letters flooding the studio mailbox each day in 1951, Zanuck struggled to respect Monroe both professionally and as a person. In private, he often dismissed her as a dim-witted individual, purely a photogenic talent and not a serious performer. But this was not an opinion shared by all her colleagues. Joseph Schenck, elderly co-founder of Fox and one of its most influential board members, was adamant that she be cast as the lead in an upcoming thriller based on Mischief, a novel by Charlotte Armstrong.

Alternatively titled Night Without Sleep and eventually dubbed Don’t Bother to Knock, the planned film would follow a single eventful night at the fictional The McKinley Hotel. Nell Forbes, a disturbed young woman related to the building’s elevator operator, is entrusted with babysitting a small child. Meanwhile, another guest, an airline pilot staying in a room nearby, becomes momentarily intertwined with her life— triggering shocking results.

Darryl Zanuck (1902-1979) had produced three films that won the Academy Award for Best Picture by 1952.

Schenck had taken a personal interest in Marilyn Monroe’s career. Rumor around the office was that they were close… very close. Whatever the reason, Schenck seemed to believe she was capable of headlining her own picture. Fox’s president Spyros Skouras agreed. Zanuck resisted.

To his credit, Monroe was about six years older than the character Nell was intended to be. She was also primarily known for sultry bit parts— not dramatic roles. Perhaps sensing he couldn’t outright veto Schenck’s decision, Zanuck made a pragmatic counter-move. He insisted that Monroe prove herself in a screen test. If she failed, that would justify finding another actress. If she succeeded, at least he could say he’d ensured she was up to the task.

Monroe prepared with pathological dedication. Reportedly, she stayed awake for forty-eight hours straight, trying to summon the jittery, on-edge mentality required for the role. On the big day she arrived with her acting coach. The outcome was a raw, intense audition that impressed even the skeptical Zanuck. He green-lit the project, the future legend’s first star vehicle.

Marilyn Monroe’s performance in Don’t Bother to Knock is sometimes cited as an early example of so-called “method acting.”

Still, his lack of enthusiasm for her manifested in other ways. He decreed that the film be produced quickly and cheaply. However, not all sources agree on exactly how shoestring the budget was. For example, biographer J. Randy Taraborrelli argues that Fox did attach some of its top talent. Daniel Taradash, who would win an Oscar in 1953 for From Here to Eternity, wrote the screenplay. Veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballard was hired to shoot it and respected composer Alfred Newman oversaw the score. But according to Donald Spoto, another biographer, the budget “must have established a new low in Hollywood.” It was about $2 million. The truth, perhaps, lies somewhere in between. Zanuck didn’t drown the production in cash and fanfare but he wasn’t interested in sabotaging it either. He assigned solid professionals and demanded they adhere to a tight schedule. Producer Julian Blaustein ensured his requests were met and the entire story was shot on the studio lot— where Fox regulars constructed a credible hotel setting.

Charlotte Armstrong Lewi (1905-1969) wrote 29 novels during her lifetime, including Mischief in 1950.

Into these developments stepped director Roy Ward Baker. An Englishman in his mid-thirties, he had honed his skills in the British film industry, working on wartime documentaries and later feature films. Morning Departure, a tense submarine drama he helmed starring John Mills, caught Zanuck’s attention in 1950. Always on the hunt for new talent, he brought Baker to Fox on a three year contract. His first assignment was I’ll Never Forget You, a period fantasy. Because the film was shot in England, Don’t Bother to Knock became his first U.S. film.

Roy Ward Baker (1916-2010) on set with Marilyn Monroe during filming in late 1951.

Like Zanuck, Baker had misgivings about casting Marilyn Monroe. He thought she was too physically mature to play a frail, former mental patient. But when it was made clear once again that Joesph Schenck and the front office wouldn’t budge, Baker, like Zanuck, swallowed his doubts. Later, in interviews, he admitted that he understood Don’t Bother to Knock was something akin to a last chance for Monroe. He noted that, at the time, she had been in about fifteen motion pictures without “breaking out”— so if playing Nell Forbes failed to earn her signifiant accolades, her career may have run its course.

Baker met his leading lady for the first time to brainstorm her look with the wardrobe department. Billy Travilla, a costume designer and friend of Monroe’s, was there as well. Collectively they decided to dial down her trademark glamour for the role. “we made her look as plain as possible,” Baker recalled, “all of which made her look, if anything, more attractive.”

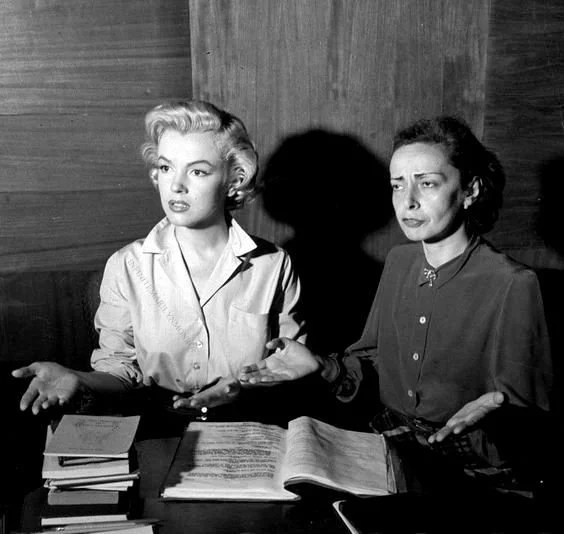

That December, another individual made her presence known behind the scenes. Natasha Lytess was Monroe’s German-born acting coach, the same one who had accompanied her to the screen test. They met in 1948, while the actress was under contract with Columbia Pictures. Lytess was the head drama instructor, assigned to work with Monroe that year on Ladies of the Chorus, a B-muscial in which she had a small part. A powerful bond was forged between them. Lytess saw potential in the fledgling performer. Monroe, hungry to learn and deeply insecure, latched onto her teachings. When her contract lapsed, she expressed a desire to continue their collaboration. Within a few years, Lytess was more than just a pedagogue to the ambitious bombshell. She was her confidante, quasi-therapist, and all-around guru.

Starting with Clash By Night, shot back-to-back with Don’t Bother to Knock, Monroe began to demand that Lytess join her on set. Her contract with Fox didn’t officially stipulate a personal coach on the payroll, but Monroe wouldn’t hear otherwise— even if it meant paying her out of her own pocket and sneaking her onto the soundstage.

Natasha Lytess (1911-1963) coached Marilyn Monroe until 1956, when the actress abruptly fired her— possibly due to her overbearing and obsessive behavior.

Baker was forewarned about Monroe’s growing dependency on her associate. Before production began, she made a formal request for access to the shoot on Lytess’s behalf. It quickly ascended chain of command until it reached Darryl Zanuck, who’s response was an unequivocal and predictable, “No.”

In a letter dated December 10th 1951, addressed to the actress at her Beverly Hills residence (which she shared with Lytess), the studio mogul called her request, “completely impractical and impossible.” Clearly referencing Lytess (though not by name), he warned, “You have built up a Svengali and if you are going to progress with your career and become as important talent-wise as you have publicity-wise then you must destroy this Svengali before it destroys you.” He finished by reminding her that she’d been cast “as an individual,” implying that her own instincts— not Natasha Lytess’s— were what the studio expected her to use.

Monroe, of course, brought her coach to work anyway. Baker generously tolerated her inclusion initially as long as she stayed out of the way. But inevitably her influence seeped in. Monroe turned to her every time Baker yelled “cut.” If she frowned or shook her head, the actress would fall to pieces and beg for a do-over. The breaking point came during a take in which she delivered a line of dialogue in a particularly odd way. Suddenly, Baker realized that she was imitating a heavy German accent— channeling Lytess instead of the character she was meant to portray. Then and there he decided to banish the “Svengali” from the set for good.

Lytess didn’t quite disappear. She continued to work with Monroe every night and Monroe still found ways to contact her discreetly during the day. In any event, as the weeks rolled on, through the holidays and into January 1952, the cast and crew held their breath, hoping she could soldier-on under the director’s new conditions.

She arrived late, throwing off the timetable and frustrating co-star Richard Widmark. “We had a hell of a time getting her out of the dressing room,” he recollected. Once they did, she often appeared flustered or unprepared. She flubbed her lines, missed her cues, performed with little energy and then overcompensated with too much. “She couldn’t act her way out of a paper bag,” Widmark said, “but she became an icon because something happened between her and the lens, and no one knows what it is.”

Richard Widmark became Marilyn Monroe’s neighbor when she and her husband Arthur Miller moved to Roxbury, CT in November 1956.

Anne Bancroft, in her debut role as lounge singer Lyn Lesley, had a different perspective. Just as nervous as Monroe, she watched as she openly battled her demons and learned from what she witnessed, rather than judged. Decades later, Bancroft praised her performance, stating that in their crucial scene together— where Lyn confronts a distraught Nell towards the end of the movie— Monroe’s authenticity caused a real emotional response from her. “It was a remarkable experience,” she said, “she moved me so tears came to my eyes.” Interestingly, according to Bancroft, Monroe actually disagreed with not just Baker’s opinion on how to play that scene, but also Natasha Lytess’s. If true, that would suggest Monroe actually did end up taking Zanuck’s advice, relying on her own instincts… at least once.

Anne Bancroft’s (1931-2005) singing voice was provided by Eve Marley.

At the end of the day, Baker’s primary directorial challenge was shaping a coherent performance from her erratic process. He exercised great patience, blowing through ten or fifteen takes by some accounts, hoping to cobble the usable bits together into a fluent whole. When he was done he sat back in his chair, cigarette in hand, ultimately satisfied with the final product.

Don’t Bother to Knock was released during the summer of 1952 on that cautiously optimistic note. Baker had weathered the storm, Monroe could breath a sigh of relief and Darryl Zanuck got the film he wanted, on time and under budget, with hopefully enough flair to recoup its cost. Thankfully, it did indeed (although just barely). Despite the mixed reviews it received, the movie played in theaters alongside two others featuring appearances from Marilyn Monroe: Clash By Night and We’re Not Married. This cultural saturation, following two national scandals and the start of her famously tumultuous relationship with megastar former athlete Joe DiMaggio— all of which had occurred over the course of about six months— made Monroe a household name, defining the final decade of her tragically brief life.