REVIEW: Detour

Detour: An Extraordinary Tale was a pulp novel published in 1939, written by Martin M. Goldsmith, reportedly a studio set-dismantler by day and minor Hollywood screenwriter by night. It told the story of a man who hitchhikes across America to reunite with his girlfriend in Hollywood, only to be thwarted by accidental death, blackmail and eventual ruin.

Martin Mooney, a producer from the low-budget studio, Producer Releasing Corporation (PRC), took an interest by 1944 and enlisted Goldsmith to help adapt his own book for the silver screen. That October, a film treatment was submitted to the Production Code Administration— infamous enforcers of the “Hays Code” since 1934. Several scenarios were swiftly flagged as unacceptable and changes were prescribed. First, a classic: no crime should go unpunished. Joseph Breen, director of the PCA, informed the studio that “it is absolutely essential that at the end of this story Alex,” referring to protagonist Alexander Roth, “be in the hands of the police, possibly having been picked up by a highway police car as he was hitchhiking.”

“Breening,” named after PCA director Joseph Breen, was a name given to the process by which he would vet storylines, change dialogue and demand the removal of footage.

Breen also demanded the removal of any hint that Vera, the femme fatal, was a prostitute. She could only be portrayed as a petty criminal, and the film had to avoid suggestion of a sexual relationship between her and the unmarried Roth while they traveled together and shared rooms. Finally, the PCA warned that if any part of the story were set in Hollywood, it must not disparage the motion picture industry in any way.

Goldsmith reworked the script to fit the administration’s requirements. Early drafts attempted to retain some of the novel’s original, two-pronged narrative style, in which Roth’s journey is laid out alongside his girlfriend Sue’s struggles working as a carhop in Los Angeles while predatory agents and producers try to exploit her at every turn. This was determined to be both cumbersome and financially impractical for the “Poverty Row” studio. A framing device set in a Nevada diner and complex flashbacks from Al’s perspective appeared in a synopsis of the script dated December 29th, 1944.

Producers Releasing Corporation, the smallest of the eleven film companies in “Golden Age” Hollywood, was located at 1440 N. Gower St.

In February 1945, the PCA signaled partial approval, but issued a few further tweaks— certain character’s death scenes needed to be toned down, as well as the Vera character’s alcoholism. A line about “frying” in the electric chair needed to be removed. The protagonist’s name would also be changed to the more generic Al Roberts by the time PRC’s production apparatus moved forward with the project that summer, perhaps to avoid an antisemitic response.

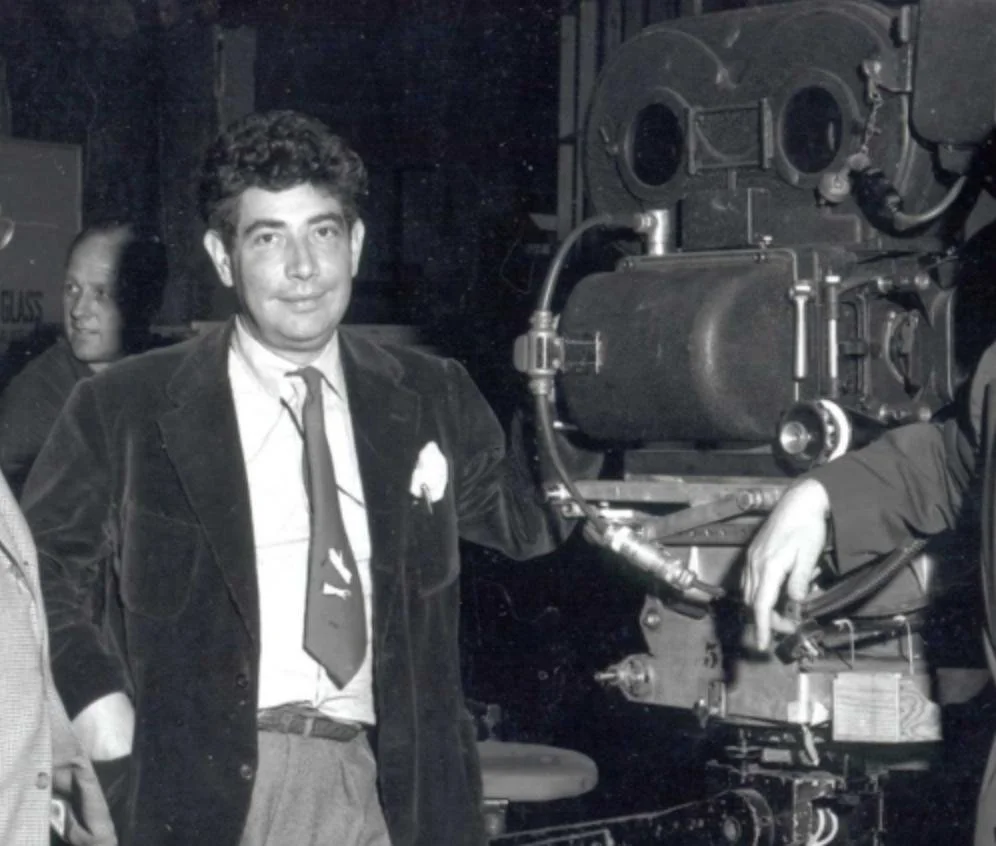

Edgar G. Ulmer was ultimately be selected to direct Detour. Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1904, he had worked on theater productions with Max Reinhardt and F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu), and after emigrating to America he directed the stylish horror hit The Black Cat for Universal. A scandal (he fell in love with a producer’s wife, who then became his own wife) led to his ostracism from the major studios. Ulmer thus spent the late 1930s making indie films in New York (mostly Ukrainian and Yiddish language productions). During World War II, he was hired by PRC. Ulmer later referred to himself as “the Capra of PRC,” since he practically ran the studio’s low-budget unit from a technical standpoint.

He assembled a small, efficient cast and crew. Benjamin H. Kline, a trusted colleague, served as cinematographer. Elmer’s usual collaborator Eugen Schüfftan was too expensive. For the lead actors, PRC drew from a pool of available B-movie talent. Tom Neal was cast as Al Roberts. He was a former boxer, groomed as a leading man at MGM and RKO but never quite lived up to what they saw in him. By the 1940s, he was working mostly on lower-budget films. Earlier in 1945 he had starred in PRC’s seedy Crime, Inc.— directed by Lew Landers.

To play Vera, Ulmer chose Ann Savage. Only 23-years-old, Savage (born Bernice Maxine Lyons) had spent some time playing brash, antagonistic roles for Columbia Pictures. She had worked with Tom Neal a year prior, on Two-Man Submarine— also directed by Lew Landers— and appeared in PRC’s Apology for Murder, set to release in September 1945.

According to Savage, Neal’s inappropriate behavior, including putting his tongue in her ear, led her to slap him and resulted in them only speaking when required for filming.

Claudia Drake, a singer-actress, was cast as Sue Harvey (the protagonist’s wife). She lent her own voice to the film’s torch song. Edmund MacDonald, a character actor, was hired for the role of Charles Haskell, Jr.— a secondary sort of antagonist. Haskell’s sudden and accidental death is the film’s major turning point, forcing Al Roberts, fearful of being mistaken for a murderer, to make a serious of bad decisions that lead him to Vera’s manipulative clutches.

A strange note: Lew Landers, who I've mentioned two times previously, was a prolific B-film director, apparently slated to helm Detour originally. Production records show Landers was paid $3,000, whereas Ulmer received only $750. One theory is that Ulmer, being on PRC’s payroll, did most of the prep work and planned to shoot the film but PRC attached Lander’s name for contractual or marketing reasons. Another possibility is that Landers was initially set to direct, but was transferred to a different PRC film, Shadow of Terror. Poverty Row films were normally fluid— for example, in Shadow of Terror PRC hastily spliced newsreel footage of nuclear testing into the film to make its villain’s “explosive formula” seem like a reference to the atomic bombs dropped on Japan that August. A mid-stream director swap on Detour would not be surprising.

Principle Photography began on June 11th 1945. Ulmer later boasted that he shot the film in six days, but production records suggest that was exaggeration. In reality, Detour was filmed in about eighteen days. That’s fourteen on soundstages, and a few more on-location. Claims have also been made that the film was made for as little as $20,000, but archival documentation shows the final cost was more like $117,226, nearly $30,000 over its initial budget allotment.

Even still, Ulmer employed every trick in the book to minimize costs. He shot many scenes in long takes, and only one or two at most. Only a few simple sets were built, like a nightclub interior, a dingy hotel room and a used-car lot office. Ulmer and Ben Kline compensated for their restraints with expressive lighting and clever framing. For the road sequences, Ulmer relied on rear-projection. Tom Neal and other actors sat in a stationary car on a soundstage while pre-filmed footage of highway scenery played behind them. In some shots of Al hitchhiking, the film negative was flipped, causing cars to appear as if they were driving on the wrong side of the road. The most likely explanation is that the director initially shot Al traveling left-to-right across the screen, but later realized that for a journey from New York to California, the conventional screen direction was right-to-left— so he inverted the footage in post-production.

After signing his long-term contract with PRC, Edward G Ulmer was put to work directing a series of short advertising films for Coca-Cola.

Noir aficionados today often cite Ann Savage’s performance as one of the most memorably abrasive villainesses in screen history. This may have been caused by the speed of the shoot injecting a feeling of raw immediacy into the actor’s portrayals. She delivers her dialogue at a machine-gun pace, with a harsh grating edge to her voice that makes the character Vera seem perpetually on the verge of either violence or hysteria. Her entrance is a prime example: Al gives the ragged young woman a lift and for a time, she appears passed out in the passengers seat. Suddenly, she bolts upright and glares at him with wild eyes, spitting out, “where did you leave his body? Where did you leave the owner of this car?”

Few femme fatals in noir are as unrefined and brutal as Vera. She’s less a sly temptress and more a brazen force, a woman whose life on the margins has made her vicious. Yet, Savage conveys subtle shadings of vulnerability. She has a cough, for instance, that hints at illness. If taken at face value, it would make her desperation even more poignant, and in rare moments when she isn’t berating Al, a glimmer of sadness or fear can be seen crossing her face.

Ann Savage’s father, a military officer, died when she was four-years-old.

After filming wrapped that summer, 1945, Ulmer edited Detour quickly. The finished product barely ran sixty-eight minutes, indicating how ruthlessly he pared it down to its essentials. PRC released the film on November 30th of that same year. As a B-picture, it opened in second-tier theaters and grindhouses, often as the lower half of a double bill. The poster art emphasized the film’s lurid, dangerous appeal, but PRC’s publicity resources were scant. Most mainstream critics ignored it. The New York Times, for example, never bothered to review it. To the industry, Detour was just another minor melodrama in an overcrowded field of post-war crime thrillers. The film may have made back its meager budget in modest bookings, but it soon disappeared from theaters without a trace. By 1946, it was largely forgotten by the general public.

Tom Neal continued to act in low-budget films for a few years, but his personal life soon eclipsed his professional one. In 1951, his jealous assault on actor Franchot Tone in a fight over actress Barbara Payton made headlines and effectively ended his career. Two years later, he left Hollywood, and a bizarre, grim epilogue unfolded. In 1965, Neal was arrested and convicted of manslaughter for shooting his third wife, spending six years in prison before he was paroled. He died of heart failure shortly after his release, in 1972.

In 1934, Tom Neal was briefly engaged to Inez Martin, the former mistress of murdered mobster Arnold Rothstein.

Ann Savage’s career continued along much the same lower-tier trajectory. By the early 1950s, she had grown frustrated by the lack of opportunities for her, married and retired from the industry. Only decades later, when Detour achieved cult status, did she resurface to give interviews about the film. Claudia Drake also left Hollywood by the end of the 1940s. Edmund MacDonald unexpectedly died at age forty-three in 1951.

Edgar G. Ulmer stayed at PRC until it was absorbed by Eagle-Lion Films and he was hired to direct Ruthless (1948), a complex drama about an unscrupulous tycoon. It would give him a chance to show what he could do with more resources and a distinguished cast, but still it did not catapult him into the A-league. As the studio system declined, Ulmer switched to ultra-cheap sci-fi and genre flicks. “I have nothing against commercialism,” he would say, “but you cannot outweigh the creative urge.”

While Detour was overlooked in the United States, European cinephiles recognized its significance immediately. French critics in the late 1940s praised it for its unflinching fatalism. They saw it as an American counterpart to the bleak, poetic “realist” dramas that were released in their own country throughout the 1930s. In retrospect, we can see Detour encapsulated a shifting postwar mood that more polished Hollywood films only touched upon.

World War II was over, but instead of triumphant optimism, Detour offered a vision of anxiety, aimlessness and senseless cruelty. It was out of step with what Americans were feelings at the time, but in that divergence lay its enduring power.

Citations

“Some Detours to Detour.” Criterion, Mar 21 2019.

Pangborn, M. “Film Noir and the Rise of the American Oil Regime: Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour (1945).” Journal of American Studies, 2021.

“Detour (1945): Noir’s Unlikely Masterpiece.” TheOldHollywoodGarden blog, Nov 4 2018.