“Hollywood for Dewey”

A History of Celebrity Endorsements Part 1: The Election of 1948

Perhaps this is as surprising to you as it was to me, but the first presidential candidate to utilize celebrity endorsements— an obligatory part of modern campaigns for higher office— was Republican Warren G. Harding in 1920. Silent film stars and Broadway luminaries like Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Al Jolson publicly appeared with the fifty-five year old senator from Ohio successfully portraying him both popular and modern. Ever since, Hollywood involvement in U.S. presidential elections has evolved— from the rallies and radio broadcasts of the studio-era to the social-media shout-outs of today. But one important question still remains: does celebrity support actually sway voters or simply add spectacle? Below I will be discussing the first major point of interest in this potentially long conversation, the election of 1948. More specifically, the campaign of failed two-time Republican Party nominee Thomas Edmund Dewey from New York, who enjoyed especially robust Hollywood backing that year.

Background

By the 1930s and 40s, celebrity political activism was already becoming much more commonplace than it had been when President Harding was elected. For instance, entertainers like Orson Welles and James Cagney flocked to President Franklin Roosevelt’s side in 1940 when he announced his intention to run for an unprecedented third term. Four years later when FDR launched his final bid for the presidency, the Republican Party nominated the ailing executive’s fiercest opponent yet— the previously mentioned Governor Tom Dewey.

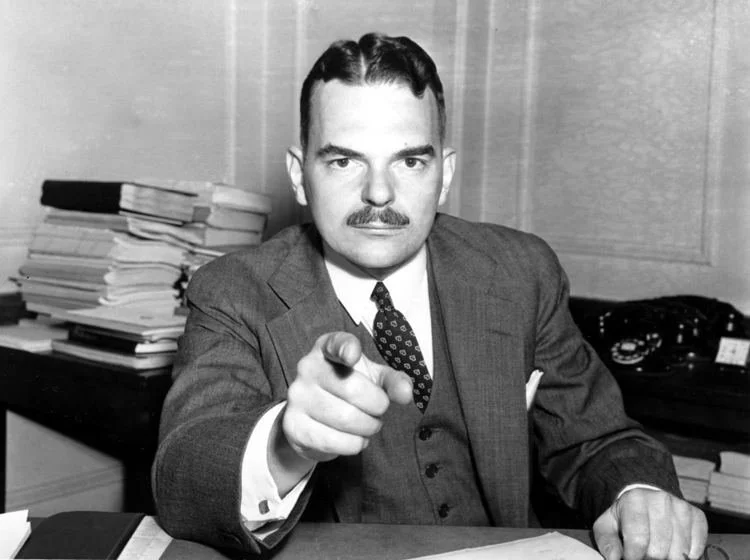

New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey (1902-1971)

Dewey had built a reputation as a crusading prosecutor battling mobsters during the Great Depression as Manhattan’s District Attorney. Hollywood transformed him into a pop-culture hero the 1930s— an early form of indirect endorsement— and soon the “Hollywood for Dewey” committee was formed by conservative movie moguls and stars to back him for the presidency. Dancer/actress Ginger Rogers (a staunch Republican and anti-communist) served as its vice chair and spent most of the 1944 campaign furiously railing against Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. On October 18th, studio chiefs David O. Selznick organized a massive rally for the governor at Los Angeles Coliseum, featuring a live elephant. 93,000 people showed up. Filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille served as master of ceremonies, and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper and Walt Disney gave short speeches. Rogers, alongside actors Walter Pidgeon, Gary Cooper, Lionel Barrymore and Randolph Scott weaved through the crowd— flashing smiles and shaking hands— lending their glitzy, prominent status to Dewey’s cause.

Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire appeared on-screen in ten classic 1930s films. Off-screen they were both active Hollywood Republicans

On the other side, more liberally inclined actors, writers and producers gathered to form the Hollywood Democratic Committee (HDC). Led by figures like Katherine Hepburn, Olivia de Havilland and Danny Kaye, they threw their weight behind FDR’s re-election campaign. After achieving their goal of defeating Dewey that November, the HDC shifted to championing other progressive causes— civil rights, nuclear disarmament— but during the next presidential election in 1948, a split occurred. Some HDC progressives were steadfast in their support for former Vice President Henry Wallace’s third party bid (more on that later), while centrists positioned themselves behind Roosevelt’s increasingly unpopular successor President Harry Truman. This foreshadowed a reoccurring theme in U.S. politics: the tension between left-wing idealism and more moderate liberalism.

The Campaign

Eventually, the 1948 competition revealed itself to be a four-way race— the incumbent Truman (Democrat) vs. Dewey (Republican) vs. Henry Wallace (Progressive) vs. Strom Thurmond (Dixiecrat). It was arguably the first truly “star-studded” race for the Whitehouse, even if it’s best remembered for Truman’s surprise victory on Election Day.

Delegates for Dewey show their support at the Republican National Convention, 1948

As the patrician favorite from the get-go (once the struggle to secure his party’s nomination was over), Dewey’s Hollywood allies were eager to push him across the finish line. Cecil B. DeMille brought back the extravagant display from the last campaign. Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Taylor, Bing Crosby and Louis B. Mayer joined Walt Disney, Adolphe Menjou and Ginger Rogers to stage parades, record optimistic radio spots and pose for Life magazine photo spreads that equated the New York governor with gloss and prosperity.

The Republican ticket was given local appeal when California’s governor Earl Warren hopped aboard as Dewey’s running mate. The GOP even funded a glamorous 10-minute campaign film The Dewey Story, a bio-pic of sorts, to reintroduce their candidate to the nation. President Truman’s campaign came out with their own, much lower budget version, The Truman Story, in response.

Needless to say, Truman’s plain-spoken style didn’t naturally attract the same caliber of silver-screen razzle-dazzle. Regardless, a handful of prominent “Golden State” personalities still stumped for him. One of them, funnily enough, was Ronald Reagan— then a “New Deal Democrat” and president of the Screen Actors Guild. Composer Frank Loesser and actress Lauren Bacall were also among those who attended pro-Truman events. Bacall and her husband Humphrey Bogart had actually organized a protest against the House Un-American Activities Committee around the same time Reagan had been called on as a friendly witness. All three appeared at LA’s Gilmore Stadium on September 23rd, 1948 to back their bespectacled commander-in-chief. George Jessel was the emcee. Photographs from that night show Bogart and Bacall grinning, seated next to First Lady Bess Truman.

Actress Lauren Bacall and President Harry Truman, 1948

Running an anti-Cold War third party campaign for the presidency— Henry Wallace’s progressive message attracted intellectuals and creatives on the left, unsatisfied with both major political parties. Among his more famous supporters were actress Ava Gardner, Paul Robeson, singer Pete Seeger and future Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern. Unfortunately for them however, the Red Scare was rapidly picking up steam. Many who endorsed Wallace were branded communists or at the very least, “fellow travelers.” Robeson and Seeger soon found themselves blacklisted from mainstream media. Gardner, after an appearance at a Wallace rally in North Carolina, was warned by Louis B. Mayer to stop campaigning to risk her career, referencing Katherine Hepburn as an example of an actress that had “ruined” herself through activism.

South Carolina Governor Storm Thurmond, the forth and final candidate, running on a segregationist “States’ Rights” Dixiecrat platform, drew little interest from Tinsel-town. Mainstream media may have been iffy on Truman but endorsing a pro-Jim Crow revolt was far from a valid alternative. The film colony in 1948 was integrated, mostly. Even John Wayne, Hollywood’s leading star on the right, preferred the moderate Thomas Dewey over Thurmond. So, Thurmond’s campaign is notable as the only one of the four to lack a single celebrity endorsement— a pattern that has generally held for overtly extremist candidates in U.S. history.

Henry Wallace (second from the left) enjoyed the support of left-wing entertainers like Paul Robeson (far-right) and Lena Horne (second from the right).

The Result

On Election Day-eve, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello’s iconic “Who’s on First?” bit was nationally broadcast over the radio as part of the “Dewey-Warren Bandwagon,” deployed to drum up enthusiasm one last time for what most of America believed was a foregone conclusion. But the next morning, they awoke to scores of stunned political pundits and pollsters— scrambling to figure out how Truman had pulled of one of the greatest election surprises of all time. He had trounced Dewey, while Thurmond and Wallace trailed far behind. So did Hollywood make an impact at all? It’s hard to say.

Celebrities undoubtedly helped to draw crowds and media attention, and they certainly drilled in their opinion that Dewey was the most impressive candidate in the race. Republican rallies in 1948 were exciting, monumental cultural events— but all the spectacle and confidence may have actually backfired. Voters, perhaps assuming Dewey would win with or without their participation, might have chosen to stay home instead. Additionally, and this will resonate with those of us who’ve paid attention to elections in the 21st century especially, Hollywood’s aggressive glittery push for Dewey may have underscored a deep disconnect with the working-class, struggling with postwar economic realities.

November 3rd, 1948— One day after his upset victory, Truman holds up an erroneous banner headline on the front page of an early edition of the Chicago Tribune.

Inflation was a concern, and there was a housing crisis driven by returning GIs. Despite Truman’s veto in 1947, the Republican controlled 80th Congress had passed the Taft-Hartley Act— sharply curtailing union power by allowing states to pass “right-to-work” laws, banning secondary strikes and requiring union leaders to swear they weren’t communists— sparking protests. At a time such as this, Truman’s anti-elitist messaging and whistle-stop tours across the midwest appealed to voters who saw Dewey’s lavish fundraisers as increasingly gaudy affairs.