Ambassador Andropov and the Hungarian Uprising

How a Young Soviet Bureaucrat Made a Name for Himself

In the fall of 1956, as Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to crush a countrywide uprising— an engagement that left thousands dead and horrified the West— a wiry, bespectacled diplomat named Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov stood on the precipice of a pivotal moment that would significantly impact his personal life and ripple down through history.

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (1914-1984)

Unexpectedly promoted as a young, Communist Party bureaucrat to the status of “Ambassador to Hungary” a year prior, Andropov was instrumental in persuading Khrushchev, the leader of the USSR at the time, to militarily intervene in the ongoing crisis. He then successfully stalled reformist Premier Imre Nagy, facilitated his capture as the smoke settled, and was rewarded for his unwavering loyalty to his country and party with rapid elevation. The career he subsequently embarked on was characterized by his undeniable strategic acumen and ideological contradictions. Eventually, it climaxed with a brief stint at the top of the Soviet hierarchy when he was elected General Secretary in 1982, fifteen months before dying of kidney failure.

Regardless, Andropov perplexingly remains a minor character in the annals of history, at least from a Western perspective. Overshadowed by his infamous predecessors, as well as his controversial successors— it is my contention that an overdue comprehensive analysis of Andropov’s life would offer critical insights into the ideological underpinnings that have shaped, and continued to guide, Russia’s trajectory. Notably, he identified numerous problems with the Soviet political system that had been ignored by his colleagues and sought reforms that would be implemented down-the-line by his protégé Mikhail Gorbachev during the perestroika movement, although to a more radical extent than Andropov likely would have if he’d lived to see them through. Additionally, his legacy of disciplined, security-centric governance still resonates, seen in the polices of long-term 21st century Russian Federation president, Vladimir Putin— his former subordinate in the KGB. Below, we will first cover his early life and rise to prominence within the Communist Party. In the posts that will follow, we’ll discuss how his late Cold-War era activity affected civilian life inside and outside of the USSR and shaped our modern cultural understanding of the Soviet Union. Then, we will cover his ascendancy to General Secretary and the authoritarian behavior he displayed while inhabiting that role in the early 1980s. Finally, we will end off with a deeper look at Andropov’s place in world history as time provides us with ever-greater distance from his tenure as head of a dying superpower.

Early Life

The exact circumstances of Andropov’s birth and even his true name seem to be in dispute, since differing sources suggest his birth certificate has either been preserved or lost but June 15th, 1914 is the date that is most often provided. He likely did not remember his biological father, Vladimir Konstantinovich, who may have died from typhus during the Russian Civil War that began shortly after Andropov was born, although again, this is not certain. According to some, Vladimir was a railway telegram operator. Others say he was a commercial auditor. His mother Evgenia Karlovna married her second husband near the end of the war in 1921, another railway worker, Viktor Alexandrovich Fedorov. “In 1923 or 1924,” Andropov wrote in his autobiography, “due to severe financial difficulties, my stepfather stopped studying in Vladikavkaz (formerly Ordzhonikidze) at the Institute of Communications and came to live at Mozdok Station of the North Caucasus Railway. There, he first worked as a building superintendent, and then as a sanitary instructor.”

“Yuri-Grigory”, an unusual double name in Russia, graduated from a railway vocational school in 1931 and went to work as a telegraph clerk and a cinema projectionist during his teenage years. He joined the Komsomol (Young Communist League) and quickly climbed the internal ladder. By 1937, he was in charge of the group’s department in the Yaroslavl Region, and was elected First Secretary of the Yaroslavl provincial Komsomol committee the following year. Partially contributing to his ascendancy was the concurrent situation across the USSR. Joseph Stalin’s Great Purge, which led to nearly 700,000 executions and 116,000 deaths inside the Gulag labor camps, created opportunities for communist youths to move up in the system— provided they showed absolute loyalty to the cause.

Committed, competent and respected by his superiors, Andropov was sent to the newly formed Karelo-Finnish Soviet Republic along the USSR’s northwestern border with Finland in March 1940. World War II had broken out the previous September and a conflict between the Russians and their Finnish neighbors referred to as the “Winter War” had ended with the ceding of the territory to the Soviets after the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty on March 12th. The Karelian population was almost entirely evacuated following this and it was resettled by the communist nation. Upon his arrival, the 25-year-old Andropov got to work in his new position as First Secretary of the Komsomol Central Committee of Karelo-Finnish SSR, allying himself with Finnish exile and chair of the Karelian Supreme Soviet Otto Kuusinen. As stated by Victor Herman of Wayne State University, “Kuusinen,” who had been selected by Stalin to lead the republic, “apparently did not realize or appreciate the intense patriotism of his fellow Finns who lived in free Finland, but he did recognize the ability of young Yuri Andropov and became his mentor in higher Party circles in Moscow.” Kuusinen’s personal political philosophy was of course Marxist-Leninism, but it ran counter to Stalin’s centralized authoritarian version in his support for peaceful domestic reform and deep investment in the global spread of socialism. It’s his influence that probably sewed the seeds for Andropov’s more defensible beliefs and policies.

A Red Army Tank in Finland during the Winter War (1939-1940)

The next year, 1941, would bring a major hurtle for Andropov when Finland retook the territory during the German invasion of the USSR, and he found himself in the middle of a war zone. He turned himself into an organizer of local partisan detachments and resisted the occupation by coordinating guerrillas assaults behind enemy lines. During this period, he was given plenty of experience with secretive, clandestine operations and more than enough opportunity to hone his rigid, disciplined approach, applied later most infamously during his work in the KGB.

After the enemy was removed from Karelia in 1944, Andropov became a bureaucrat once again. He was Second Secretary of the Petrozavodsk city party committee and then Second Secretary of the Communist Party of the entire Karelo-Finnish SSR. As the war came to a close, he helped to rebuild the republic and re-establish Soviet authority, fortifying a solid reputation as a loyal Stalinist while also earning a formal higher education at the Karelo-Finnish State University in Petrozavodsk and the Higher Party School in Moscow. In 1951, he was invited to work in the central apparatus of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the sole governing political party in the country. Acquainted with other rising communists and possessing a network of contacts due to his affiliation with Otto Kuusinen (who would be elected by the Central Committee to serve on the Presidium the following year), Andropov was placed in a department that supervised the lower-ranking communist parties in the Union Republics. Two years later, as the USSR re-defined itself in the wake of Stalin’s death, he began working at the Soviet Embassy in Hungary as a counselor and chargé d’affaires (an official that may temporarily take the place of an ambassador). The following year, 1954, he was made Hungarian ambassador. Tasked with keeping a handle on the disintegrating regime of Stalin-disciple Mátyás Rákosi, Andropov taught himself the Hungarian language and familiarized himself with Hungarian local politics— skills that would soon be of use in the coming calamity.

Finnish-born communist Otto Wilhelm Kuusinen (1881-1964) mentored young Yuri Andropov and facilitated his rise to power.

But quickly, before we cover the final act of this post, for the sake of providing a look as all-encompassing as possible, let’s back-track for just moment. As you may have noticed, we’ve only been covering Andropov’s career, but aside from his few at-work friendships and alliances like Kuusinen, we’ve barely touched upon his home life. In truth, there is little cover in this area. Andropov, by all accounts, seems to have been a very career-focused individual. We know he was married to a woman named Nina Engalycheva in the late 1930s. She had two children with him, a boy and girl, and when he moved to Karelia they did not join him. That year, 1940, he met his another woman in Petrozavodsk while they were both working for the Komsomol. Her name was Tatyana Filippovna Lebedeva. He divorced his first wife and married Lebedeva in the summer of 1941. They had two children, also a boy and girl, named Igor and Irina. After his transfer in 1951, they moved as a family to Moscow and then to Budapest in 1953, settling into a residence across the street from the Soviet Embassy. What Tatyana experienced there, particularly following a watershed moment on October 23rd, 1956 would turn her into a recluse, suffering from acute headaches, hypertension and a fear of crowds for the rest of her life.

The Hungarian Revolution

Apologies, bare with me now while I catch you up on some Hungarian history for context…

At the end of World War II, the Kingdom of Hungary was a multi-party democracy in the geopolitical sphere of influence of the Soviet Union. Despite only receiving 17% of the vote in the 1945 parliamentary elections, the Hungarian Communist Party was able to wrestle control away from the coalition government by 1949 when they merged with the Social Democratic Party of Hungary, establishing the Hungarian People’s Republic on August 20th of that year. Economically, the new nation was based on the USSR (meaning the nationalization of the means of production) and the USSR was permitted to station the Red Army inside their borders.

Mátyás Rákosi, who headed the government during its early years purged seven thousand political dissents from the Communist Party, accusing them of being “Western agents”. In his grip, Hungary would soon be known as the most oppressive regime in the Eastern Bloc. He conducted “show trials”, forcibly relocated thousands of non-communist Hungarians and then killed them, deported them to the USSR or threw them into concentration camps. Church leaders were replaced by communists. The study of the Russian language and communism were made mandatory in primary schools and at the university-level.

Concurrently, the standard of living in Hungary fell off a cliff. Compulsory financial contributions aimed at industrialization reduced deposable income for workers and bureaucratic mismanagement of the distribution of resources caused food shortages. The government was also paying war reparations at the time to the USSR, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, which compounded the economic issues that were already snowballing. Participation in COMECON (the Soviet sponsored Council of Mutual Economic Assistance) prevented trade with the West.

With haste, the Hungarian people became reasonably dissatisfied and decidedly anti-Soviet.

After the death of Stalin on March 5th 1953, the Communist Party of the USSR began a process of “de-Stalinization”, loosening restrictions that had been put in place by the late-dictator. This was extended to other allied communist countries in the Warsaw Pact, like Hungary, where Rákosi was removed as prime minister and the reformist Imre Nagy took his place. Unfortunately however, Rákosi was not completely dethroned and remained General Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party, a position he used to frustrate and block Nagy from enacting any of his policies. By April 14th 1955, Prime Minister Nagy (who was also out of favor in the USSR) was stripped of his Communist Party membership and kicked out of office. He refused to resign or perform the typical communist penance on his way out the door. But Khrushchev, the new leader of the USSR who had been spearheading “de-Stalinization”, was not satisfied with seeing the return of Rákosi and thus had him dismissed as General Secretary and replaced by Nagy’s Minister of the Interior, Ernö Gerö during the summer of 1956.

Months later, at the University of Szeged on October 13th, a group of students re-established the Union of Hungarian University and Academy Students, which had been banned by Rákosi. A law professor formalized it soon after, proclaiming a manifesto with ten anti-Soviet demands including free elections and the removal of Soviet troops from Hungary. Other Universities did the same within days. On October 23rd, twenty thousand protestors met at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics beside a statue of Józef Ben, a Polish and Hungarian hero. Earlier that year, an assault by the Polish Army on protesting workers in the Polish city of Poznań had resulted in the successful procurement of concessions from the USSR regarding political reform, trade and the removal of troops, and Hungarians clambered for the same. The protesters began to chant over and over “This we swear, this we swear, that we will no longer be slaves.” Enrö Gerö broadcasted a speech in response, condemning their demands. Enraged, they destroyed a massive monument to Stalin that had been erected in 1951.

A pair of boots was all that remained of the Stalin Monument in Budapest, destroyed on the night of October 23rd, 1956

A crowd then gathered outside the Magyar Radio building. When they heard rumors of the arrest and detainment of students who had entered and attempted to broadcast their political demands, the situation escalated. The secret police threw tear gas grenades from the windows and began to fire at the crowd. When they ran empty, they tried to smuggle in ammunition and weapons using an ambulance but it was hijacked by the protestors who took the supplies for themselves. Police vehicles were set on fire. The Hungarian Army sent soldiers for support but some of them tore off their red-star insignias and joined the crowd.

The Soviets Get Involved

Ambassador Yuri Andropov had been closely monitoring the developments in Hungary since the previous summer, alerting the Kremlin to the “alarming” ferment as it evolved. Around 5:00 pm on October 23rd, with the events unfolding, he called Lt. Gen. Pyotr Lashchenko— a Soviet military commander in Hungary— and urged him to “send his troops to liquidate the disorder in Budapest.” But Lashchenko refused, stating he had no authority to intervene without a direct order from Moscow. The next day, under a request signed by Hungarian Prime Minister András Hegedüs, defense minister Georgy Zhukov provided that order. Red Army tanks were stationed outside the parliament building and soldiers took over the bridges and crossroads, controlling access to the city by 12:00 pm. Revolutionaries barricaded the streets in response, preparing to defend themselves against the Soviets if necessary.

The next day, more fighting erupted in Budapest. Andropov cabled the Foreign Ministry in Moscow requesting to “temporarily stop special mail deliveries,” to the embassy “because of the dangerous situation.” High level Russian officials including Presidium members Anastas Mikoyan and Mikhail Suslov arrived, but struggled to land due to the unrest. Alongside Andropov, they attended an emergency meeting of the Central Executive Committee of the Hungarian Worker’s Party in their headquarters on Akadémia Street. Ultimately, to quell the evolving crisis, it was decided amongst those present that Imre Nagy would be reinstated as prime minister. Regardless, the disorder continued. The next day, outside parliament, secret police once again fired into a crowd that included women, children and elderly civilians. Secretary Gerö fled to the USSR, under threats of violence from the protesters for calling in the Soviet troops. János Kádar, a more moderate communist, was approved by Moscow as his replacement. According to some sources, it was Andropov who suggested this reshuffle.

Imre Nagy, once again in charge of the government, called for peace. The streets remained perilous, with pro-Soviet officials still regularly attacked by insurgents, but soon a shaky ceasefire descended on the ruined city. On October 27th, Mikoyan and Andropov invited Nagy and Kádár for a private discussion. Rebelling against the Soviets, Nagy pushed for democratization and the departure of the Red Army. Andropov informed Moscow afterwards that revolutionary councils and committees had replaced communist authorities in seventeen of the country’s nineteen provinces. Spooked, Moscow officials began to plot a new course.

From inside the Soviet Embassy, two days later, Andropov witnessed the brief period of calm shatter, as an anti-communist mob attacked and lynched secret police during an assault on the Hungarian Party’s Central Committee headquarters, hanging them from lamp posts. Fearing for the safety of his people, again he contacted Moscow to alert them about the situation and quietly prepared for the possibility of evacuation if the protesters manage to topple the existing government or storm the embassy. Future colleges in the KGB would note that it was this moment during the revolution that “haunted” him “for the rest of his life.” His conviction that only force could prevent a counter-revolution, which developed subsequently (referred to as his “Hungarian complex”), was also a consequence of this.

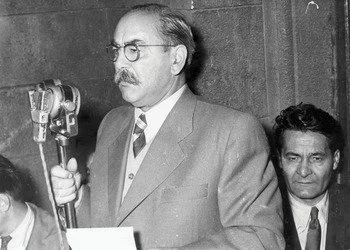

Imre Nagy (1896-1958) assumed control of the Hungarian People’s Republic during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

As this occurred, Imre Nagy made even grander concessions, promising to free political prisoners and legalize non-communist parties, expressing an end goal of forming a coalition government as soon as possible. On October 31st, Khrushchev conveyed the Soviet Presidium (which still included Andropov’s buddy Otto Kuusinen). They decided to intervene for a second time immediately, and sent additional troops to Hungary’s border. Taking notice of this, Nagy declared Hungary’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact and appealed to the United Nations for protection. He summoned Andropov to Parliament and demanded an explanation for the large Soviet forces that had entered the country. Andropov apparently offered reassurances that the USSR sought a peaceful resolution, comically described as “Byzantine levels of equivocation and outright untruth.” Incensed, General István Kovács, Hungarian Army Chief, confronted him with evidence that Hungarian radar had tracked entire Soviet divisions crossing over the Eastern border, but Andropov continued to mislead the officials about his country’s intentions, and then cabled Moscow. Nagy, he said, had “threatened a scandal and resignation of the government” if Soviet troop incursions did not halt.

After a vote formalizing the Hungarian appeal to the United Nations of assistance, Kádár (who voted in favor) slipped away to join the Soviet side that night. With a showdown imminent, Andropov had his family and other Soviet dependents evacuated to a secure location (potentially Szolnik) and officially closed down all embassy operations. As the Soviets encircled the city and moved into attack positions, he maintained contact with Nagy’s personnel still feigning interest in negotiating troop withdrawal. Hungarian negotiators sent to meet with the Soviets were arrested on sight and at dawn, November 4th, the Red Army launched a massive invasion of Budapest (as well as other key regions) overwhelming the resistance within days.

On November 7th, János Kádár re-entered the city under Soviet protection and installed a new “Revolutionary Workers’-Peasants Government”, loyal to Moscow. Andropov, also under heavy guard, performed his duties as a key intermediary between the regime and the Red Army. As they snuffed out the last pockets of armed resistance, thousands died or were injured. He reported back home that the “counter-revolution” had been defeated, but still had an important role in a final bit of drama yet to play out: the fate of former Prime Minister Imre Nagy.

Rebels in Budapest, 1956

Holed up in the Yugoslav Embassy for safety with his associates, Nagy was determined to have been seeking asylum since the invasion commenced. Andropov, on behalf of the Soviet and fledgling Kádár government, provided a written assurance of safe passage if they come outside. On November 22nd, the moment they complied, Soviet agents led by KGB officer Vladimir Kryuchkov seized them on Andropov’s orders and deported them to a secret location in Romania. Some accounts suggest that Andropov watched from the embassy window and even waved goodbye as they were forced into a car. Even if that’s not true, the betrayal itself was an absolutely ruthless move from the future General Secretary. On June 16th, 1958— Nagy and his allies were tried, executed for treason and buried in an unmarked grave.

Ambassador Andropov Gets a Promotion

Ambassador Andropov remained in Budapest for a time, coordinating between Kádár and the Soviets, overseeing the continuous rooting out of remaining dissidents. In March 1957, he was recalled to Moscow after half a decade of service. Due to his “exceptionally fine work” the Presidium appointed him head of the newly created Department for Liaison with Communist and workers’ Parties— a senior role that dealt with socialist Eastern Bloc affairs.

Despite the admiration of his superiors, contemporary Kremlin insiders noted that Andropov’s hair turned visibly grayer after 1956. Although she kept her composition in public, his wife Tatyana was also shaken by her experiences, as stated earlier. She suffered nightmares, but biographies convey that the Andropov’s marriage remained strong. Tatyana provided support as Yuri struggled with insomnia and stress in the aftermath.

Soviet archives paint a picture of Andropov as crafty and unwavering, braving personal danger to ensure the USSR’s objectives were met like a preeminent party loyalist. Indeed, this is an accurate assessment and and his reputation in Moscow as such was solid from this point on, which we will explore in more detail next time. In Hungary on the other hand, to those who were aware of his duplicity, he was reviled. Word spread fast and among its citizens, he was given a nickname, whispered on the streets as he rose to ever more prominent positions of supremacy.

They called him, the “Butcher of Budapest”.